Chinese artist Wan Yun-feng’s aesthetic activism for more-than-human oceans

Nowadays, China’s maritime aesthetic often has a lot to do with its growing sea power among the world’s oceans. Beyond the empowering spectacle created by the vaunted 21st Maritime Silk Road and the numerous naval manoeuvres in the Western Pacific, some of the infrastructural developments featured as extractive tools spring up as a dominant manifesto of China’s technologised aesthetics of the sea.

In 2019, an offshore drilling rig named “Blue Whale No. 2″ was put into service (Figure 1). According to influential Chinese media The Paper, the aquatic mechanical beast is “designed and built by CIMC Raffles Offshore Engineering Co Ltd, a wholly owned subsidiary of CIMC … weighs 43,725 tonnes, is 37 storeys high and can operate in 95% of the world’s waters, with a maximum drilling depth of 15,250m” (2019). The main function of the “Blue Whale” focuses on deep-sea mining of manganese ore, crude oil, and methane clathrate (commonly known as flammable ice). Such extractive practices for China’s South China Sea resources are expected to drive China’s deep-sea industrialisation and commercialisation in the near future, and hence be closely tied to national interests. Therefore, offshore drilling rigs are portrayed as “mobile national territory” in China’s state maritime narrative, as they are tied in with the country’s overall industrial strength and development orientation.

Figure 1. Blue Whale No.2

This is just one instance of how China’s maritime aesthetic has been mobilised by its “oceanic modernisation or blue economy claims” (Fabinyi et al., 2021). With Chinese sea power gaining traction in terms of geo/aqua-politics, economics, and cultural relations in the world oceans, the growth of extractivism is taking over people’s imaginations towards the sea. This is creating an Anthropocene structure of feeling where the environment becomes a blind spot for China’s engagement with modernised, capitalised, and globalised practices and discourses, despite its official propaganda insisting on general intentions on cooperation and equality in maritime affairs. As I have mentioned elsewhere (Li, 2023), China’s maritime legal system is claimed in any public forum to be based on the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) which is often cited as an endorsement of China’s maritime practices. However, as Anna Zalik and many others argue, UNCLOS formulates the space of the oceans as an “extractive frontier” (2018, p.343). In response to the rampant extractivist discourse and its associated structures of feelings, China needs an alternative aesthetic to expand its political reckonings and social imaginaries to rebuild connections to and dependence on the non-human world over the course of modernity.

In this regard, I turn to Chinese performance artist Wan Yun-feng, who has created extensive works about vulnerable more-than-human body images in the Anthropocene, and beyond the aesthetics and narratives about China’s rise to power in the oceans. Wan’s works are mostly posted as short videos on the Chinese social media Tik-Tok and Bilibili, where he brings the more-than-human world outside of people’s vision to the forefront through fashion design, physical performance, and realistic scenes of biological suffering. Wan’s latest series is entitled ‘Protecting the Ocean – The Struggle,‘ by which he considers and presents some examples of “how ocean returns” (Probyn, 2018).

In the episode ‘Foam,‘ Wan makes a representative reference to a video clip filmed by marine conservation biologist Christine Figgener and her team in 2015 of a plastic straw being removed from a sea turtle. In a cross-posted presentation of Wan’s performance, he plunges the white plastic tube deep into his throat, empathetically acting out the pain of a sea turtle suffocating in a clog of plastic (Figure 2) The episode’s title is metaphorical, considering that foam in Chinese can stand in for both plastic and the beautiful incarnation of water. As Figgener explains, “You were able to show the suffering of a creature that was affected by a straw that someone had disposed of. Definitely that was an object that passed through human hands and made its way to the ocean” (Rosenbaum, 2018, cited in Probyn, 2020, p.179). If the turtle’s heartbreaking struggle in front of the camera warns us of the ocean’s porosity and vulnerability to human practices, Wan’s performance, in turn, demonstrates the mutuality of this impact. The straw thrust deep into the throat may be a dramatic representation, drawing attention to the fact that the human body will eventually be the last victim of its poisoning of the ocean. In other, more ordinary scenes that Wan inserts, the tidal zone of a coastal city is filled with plastic waste, with which waves are washing ashore (Figure 3). It concisely illustrates how the ocean returns to the human world. Immediately afterwards, a high-speed rising number is fixed at 176,000,000,000 on screen, a staggering indictment of the tonnes of waste we dump into the oceans.

Figure 2. Screenshot of Protecting the Ocean – The Struggle

Figure 3. Screenshot of Protecting the Ocean – The Struggle

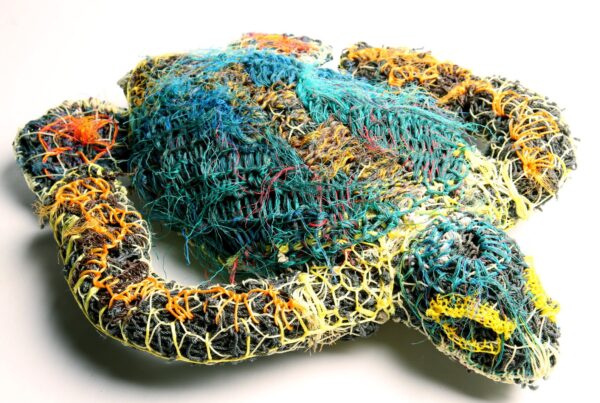

In a guest appearance on the variety show Hello! Teacher [1] in 2021, Wan highlights the ocean as a victim and absorber of plastic waste, oil pollution, heavy metal pollution and other modern/industrial by-products. In another series of performances, Wan mimics numerous sea creatures driven to their death by industrialisation in different dimensions. He makes umbrella covers out of plastic bottles to perform jellyfish, wraps nylon nets or wires around his body to demonstrate the deadly entanglement of rubbish, or blackens his skin with oil to evoke the disturbing by-products of extractivism. Furthermore, Wan juxtaposes the human body with the bodies of more-than-humans to “evoke compassion and empathy.” By doing so, Wan is insisting on activism that gives a voice to more-than-humans. As he has declared in many of his public speeches, “Animals don’t speak, so I/we speak for them.” His efforts offer an imagination to rediscover the permeability between humans and more-than-human oceans as well as their mutual responsibility and accountability.

Unlike excessive concern for recent human histories in Anthropocene thinking, Wan’s aesthetic activism is productive in providing us with alternative scales to narrate temporalities. If we return briefly to the previous narration of the “Blue Whale,“ it is not difficult to find that the extractivist sublime abounds in the rhetoric of the Anthropocene. A massive oil-extraction machine may stay in the industrial imagination provided by technological spectacle, but the oil it extracts must be unfolding in our everyday lives in more ordinary stories. The annoyance created by the mass of private cars congesting city streets and the convenience offered by a civilian airliner on long-distance travel draws the oceanic oil closer to a down-to-earth narrative. These are just a few of the embodied epitomes of the powerful synthesis of national power and modernised lifestyle that is celebrated by today’s Chinese people. They bind our imagination to one of mere modernity towards extraction. However, a drop of oil’s life is often not simply measured by the amount of time it takes to be burned for energy, but by the depth of time it takes to crystallize the ancient organic matter. We need an imagination to gain insight into different temporalities, thereby overcoming what John Clarke states in his critique on current derangement as ‘the profound tensions emerging between the apparent urgency of planetary time in the face of ecological disaster and the foot-draggingly slow time of ‘business as usual’ in the dominant political and economic regimes” (2019, p.137).

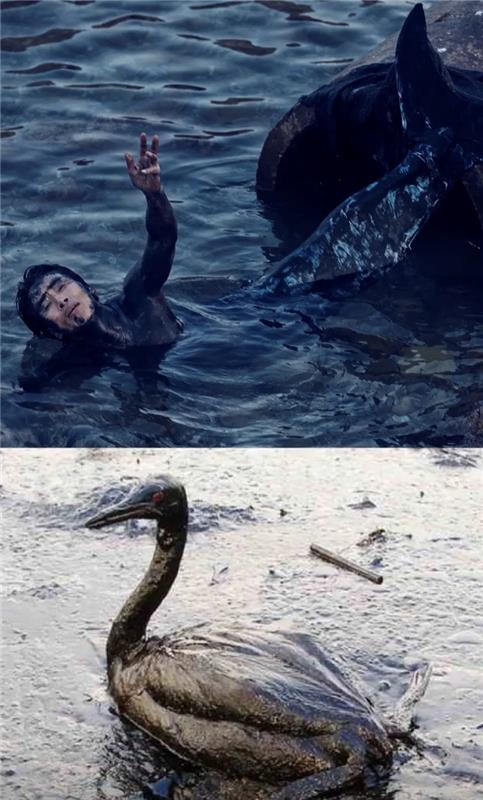

So, how could the story be told in other ways? In Wan’s latest shot ‘The Mermaid,‘ he wears a fishtail costume and paints his body black. Such a chimaera-like body reveals the hybrid subjectivity of both humans and more-than-humans in the Anthropocene. The show symbolically overlaps the blackened sea, the creatures suffocating in oil, and the polluted human world. In the following sequences, the sea creatures are soaked and encrusted by oily waters (Figures 4–5). If we can imagine oil as the crystallisation of billions of years old plant and animal carcasses, the above scenes articulate the by-products of extractivism at an intersection of multiple temporalities. Firstly, the ancient liquid corpse covers dying more-than-human bodies, creating new deaths. Secondly, the non-degradable nature of oil allows it to exist in the oceans on a much slower scale, eventually becoming toxic nodules in human and more-than-human bodies through, for example, seepage into groundwater or food chain enrichment. The story seems to be the same for other wastes that permeate the ocean—they accumulate slowly and heavily in ocean fluids over a considerable time. So far, they have gradually changed the physical and chemical properties of the ocean. As Wan highlights in ‘Plastic Jellyfish,‘ jellyfish swim in seawater over-saturated with plastic particles (Figure 6).

Figure 4. Screenshot of Protecting the Ocean – The Struggle

Figure 5. Screenshot of Protecting the Ocean – The Struggle

Figure 6. Screenshot of Protecting the Ocean – The Struggle

In ‘The Mermaid,’ Wan mobilises his polluted body to tenderly kiss and embrace the Earth (the instrument) to represent an inter-species effort to work together for the sake of the planet and the oceans that human share with more-than-humans. The initiative symbolised by his gesture is ambitious in scale – meaning that it extends in space to the entire planet or its oceans, and in time to the whole history of the planet. This seems to be a cliché that numerous environmentalist actions deploy, thus creating distance and discomfort vis-à-vis specific everyday life. But in his performances, Wan bridges these gaps in scale by offering multiple perspectives on the imagination. As we have already seen, plastic waves in seaside cities, plastic pellets swimming with jellyfish and straws that we may have casually thrown away a few days ago converge from different temporalities into the current environmental crisis. Similarly, oil relates to multiple scales. It is a fossil fuel at the frontier of extractivism, a factor in creating an imminent environmental crisis, and a chronic poison that slowly accumulates in water veins and food chains. It comes to us that there are so many things waiting to be done. However, as a first step, Wan’s aesthetic activism calls for China’s (and beyond) collaborative efforts towards more-than-human oceans. Just as Wan opens his arms to every spectator (Figure 7) after kissing the earth, his activism shuttles on different scales that require each and every one of us to expand our imaginations of the oceans and more-than-humans.

Figure 7. Screenshot of Protecting the Ocean – The Struggle

References

Clarke, J. (2019). “A sense of loss? Unsettled attachments in the current conjuncture”, New Formations, 2019 (96-97). https://doi.org/10.3898/NEWF:96/97.05.2019

Fabinyi, M., Wu, A., Lau, S., Mallory, T., Barclay, K., Walsh, K., & Dressler, W. (2021). “China’s Blue Economy: A State Project of Modernisation”. The Journal of Environment & Development, 30(2), 127–148. https://doi.org/10.1177/1070496521995872

Li, D. (2023). “Hydrothermal fluids, energy extraction, and temporal scales”. Extracting the Ocean. https://extractingtheocean.org/ocean-energies/hydrothermal-fluids-energy-extraction-and-temporal-scales/

Probyn, E. (2018). “The ocean returns: Mapping a mercurial Anthropocean”. Social Science Information, 57(3), 386–402. https://doi.org/10.1177/0539018418792402

Probyn, E. (2020). “Wasting Seas: Oceanic time and temporalities”. The Temporalities of Waste: Out of Sight, Out of Time. Taylor and Francis. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429317170

Wan, Y-f. (2021). “We’re not far from plastic humans”. Hello, Teacher!. Mango Television. https://www.douyin.com/user/MS4wLjABAAAAxeW9KEbm4Gbg2JOM4wHq_GPFPj-ha0WmtIegM6CXnBQ?modal_id=6920156112972958976

Wan, Y-f. (2023). Protecting the Ocean – The Struggle. Tiktok. https://www.douyin.com/user/MS4wLjABAAAAxeW9KEbm4Gbg2JOM4wHq_GPFPj-ha0WmtIegM6CXnBQ

Zalik, A. (2018). “Mining the seabed, enclosing the area: ocean grabbing, proprietary knowledge and the geopolitics of the extractive frontier beyond national jurisdiction”. International social science journal, 68, 343–359.

Zhou, B. (2019). “Chinese Power: ‘Blue Whale No. 2’: A powerful tool for the deep sea (中国力量: “蓝鲸2号” :独步深海的大国重器)”. The Paper. https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_4464702

Image sources

Figure 1: http://www.news.cn/photo/2021-10/19/c_1127972998_2.htm

Figure 2: Screenshot of Protecting the Ocean – The Struggle. https://www.douyin.com/user/MS4wLjABAAAAxeW9KEbm4Gbg2JOM4wHq_GPFPj-ha0WmtIegM6CXnBQ?modal_id=7242256803545861435

Figure 3: Screenshot of Protecting the Ocean – The Struggle. https://www.douyin.com/user/MS4wLjABAAAAxeW9KEbm4Gbg2JOM4wHq_GPFPj-ha0WmtIegM6CXnBQ?modal_id=7234092913691462912

Figure 4: Screenshot of Protecting the Ocean – The Struggle. https://www.douyin.com/user/MS4wLjABAAAAxeW9KEbm4Gbg2JOM4wHq_GPFPj-ha0WmtIegM6CXnBQ?modal_id=7242256803545861435

Figure 5: Screenshot of Protecting the Ocean – The Struggle. https://www.douyin.com/user/MS4wLjABAAAAxeW9KEbm4Gbg2JOM4wHq_GPFPj-ha0WmtIegM6CXnBQ?modal_id=7242256803545861435

Figure 6: Screenshot of Protecting the Ocean – The Struggle. https://www.douyin.com/user/MS4wLjABAAAAxeW9KEbm4Gbg2JOM4wHq_GPFPj-ha0WmtIegM6CXnBQ?modal_id=7235188148404276532

Figure 7: Screenshot of Protecting the Ocean – The Struggle. https://www.douyin.com/user/MS4wLjABAAAAxeW9KEbm4Gbg2JOM4wHq_GPFPj-ha0WmtIegM6CXnBQ?modal_id=7235946103428926781