Industrial fishing fleets routinely dump thousands of tons of plastic pollution into the ocean, as they are too much of a dent to the bottom line to retrieve.

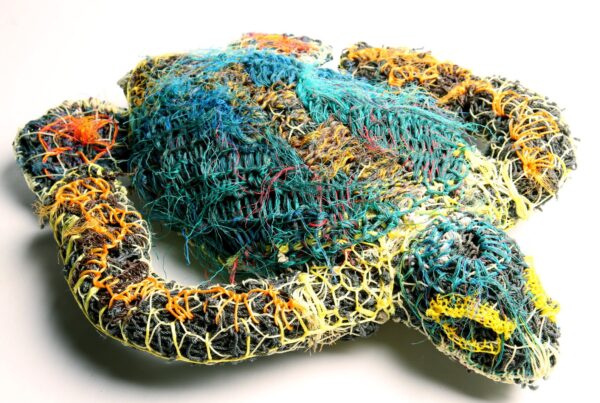

Discarded nets drift water columns and trundle across seabeds in lethal veils and clumps. Along their journey, they damage reefs and seagrass meadows and injure or kill whales, turtles, sharks and other marine animals for decades. Though known as ghost nets, the impact of abandoned fishing gear in the ocean is far from spectral. They are the most dangerous form of marine debris (TierraMar & SMaRT@UNSW) the fishing industry’s proxy predator.

One study has found that, in 2018, industrial fishers dumped or lost an estimated 100kt of derelict nets into the ocean (Kuczenski et al). The authors acknowledge that as this figure excludes nets discarded by small scale fisheries, the total is likely to be significantly more (TierraMar & SMaRT@UNSW, 2021 p.11). According to UNEP, 661,000–881,000 metric tonnes of ghost gear enters the ocean each year. Yet another study reports that ghost nets and ghost gear made up 46% of the 76,000 tons of plastic observed in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch (TierraMar & SMaRT@UNSW, 2021 p.11). By weight, 70% of floating microplastic in the ocean is attributed to ghost nets and ghost gear (TierraMar & SMaRT@UNSW, 2021 p.11).

Synthetic nets made from petrochemicals have been around since the 1970s and continue to be the standard gear of fisheries. How many decades-old nets are still adrift or snagged to reefs and rocky ledges; or tangled around the captive remains of marine animals unable to free themselves? Without sufficient monitoring and regulation, and as fisheries regimes expand, ghost nets will be a growing and lethal danger for already vulnerable ocean realms (See also Parks and Wildlife Australia).

Ghost nets also impact marine animals and lifeways on land. Across northern Australia, 95% of all identified nets have drifted from Taiwan, Indonesia, Thailand and Korea (TierraMar & SMaRT@UNSW, 2021 p.11). Tonnes drift into the Gulf of Carpentaria, carried by currents in the Arafura and Timor Seas and strong ocean tides. Once thrown ashore, and half buried in sand, the nets continue to tangle marine animals and prevent turtles from reaching nesting spots. Bleached by the sun and abraded by saltwater and sand, plastic nets and gear gradually break down, shedding micro-plastics that heat already warming shores and can change the gender mix of not-yet-hatched turtles.

References

Kuczenski, Brandon, Camila Vargas Poulsen, Eric L. Gilman, Michael Musyl, Roland Geyer, and Jono Wilson. 2022. “Plastic Gear Loss Estimates from Remote Observation of Industrial Fishing Activity.” Fish and Fisheries 23 (1): 22–33, 31.

TierraMar, and SMaRT@UNSW. 2021. “Ghost Nets. Needs Analysis and Feasibility Study for Northern Australia, Final Report.” Sutherland, 30.

Image: Hauling fishing nets out of Hawaiian waters (June 2012, Midway Atoll, Hawaii)

Photograph credit: NOAA

Image: Turtles caught in ghost gear

Photograph credit: Jane Dermer

Video: NOAA Ocean Today—’Whale Rescue’

Credit: NOAA