Industrial and smaller fishers alike routinely lose or dump synthetic fishing gear to the ocean. It is a practice that avoids the expense of retrieval and maximises profits for fisheries corporations.

Private gain comes at a cost to human publics left to invest resources and time in recovery efforts. As petroleum based synthetic nets dominated the market by the 1970s, dumping of this material has likely been occurring for over 50 years. Drifting for decades through the ocean, the impact of these ghost nets on marine animals has been lethal. As just one example, modelling by CSIRO and GNA, estimated that between 4,866 and 14,600 turtles are caught in ghost nets annually, in the Gulf of Carpentaria (Wilcox et al, 2014).

How is it that the industrial fishing regimes get to dump 661,000–881,000 metric tonnes of ghost gear into the ocean each year, some of it the size of football pitches? How is it that petroleum based, synthetic materials dominate the market for fishing gear, despite their toxicity to environments? A recent Australian investigation indicates that fisheries practices that conform to global sustainability standards still contribute to accumulating terrestrial piles of wasted synthetic nets. The nation’s largest and most valuable prawn fishery, the Northern Prawn Fishery (NPF), is certified for sustainable and well managed fisheries according to Marine Stewardship Council global standards (TierraMar, 2021). While the NFP minimises the loss of nets at sea, every year it dumps more than 20 tonnes of ‘end of life’ nets in landfill (TierraMar, 2021). According to UNEP, synthetic fishing nets take 600 years to breakdown (which really means the shedding of microplastic).

Extractive regimes continue to turn a profit while externalising their environmental costs. Marine extractive industries hunt down animal populations, pollute, drill, mine, scrape and sonically pound the ocean and their seabed. As extractive capitalist profits rise, so do the unaccounted costs of plastic, heat, toxic and sonic wastes. Legal regimes provide the enabling architecture for such exploitation and contribute to a wider extractive infrastructure of mutually supporting actors, which includes governments, supporting industries (design, engineering, construction, distribution) and investors. Extractive infrastructures also include growing numbers of human consumers, whose need for basic goods and desire for more, fuel yet further extraction.

Across the world, though, infrastructures of resistance and care come together to try to counter extractive regimes. Not-for-profits and other agencies respond by gathering evidence, raising awareness, developing resources, lobbying for regulatory change, and taking direct action such as rescuing stranded animals, retrieving extractive capitalist discards from beaches, exploring re-use options for retrieved materials, and protest. Globally, for example, there’s Global Ghost Gear Initiative, Ocean Conservancy, and UNEP, and in Australia government agencies such Parks Australia and university initiatives such as UNSW SMaRT Centre. The ocean is a significant part of such counter infrastructures, as they survive, recover, and regenerate (where they can) from the impacts of extractive fisheries. As an example, in northern Australia, tons of dangerous ghost nets drift into the Gulf of Carpentaria, carried by currents in the Arafura and Timor Seas, and strong tides. While the Gulf is a hot spot for derelict nets, the ocean also washes the nets onto the islands of the Torres Strait such as Erub and Darnley.

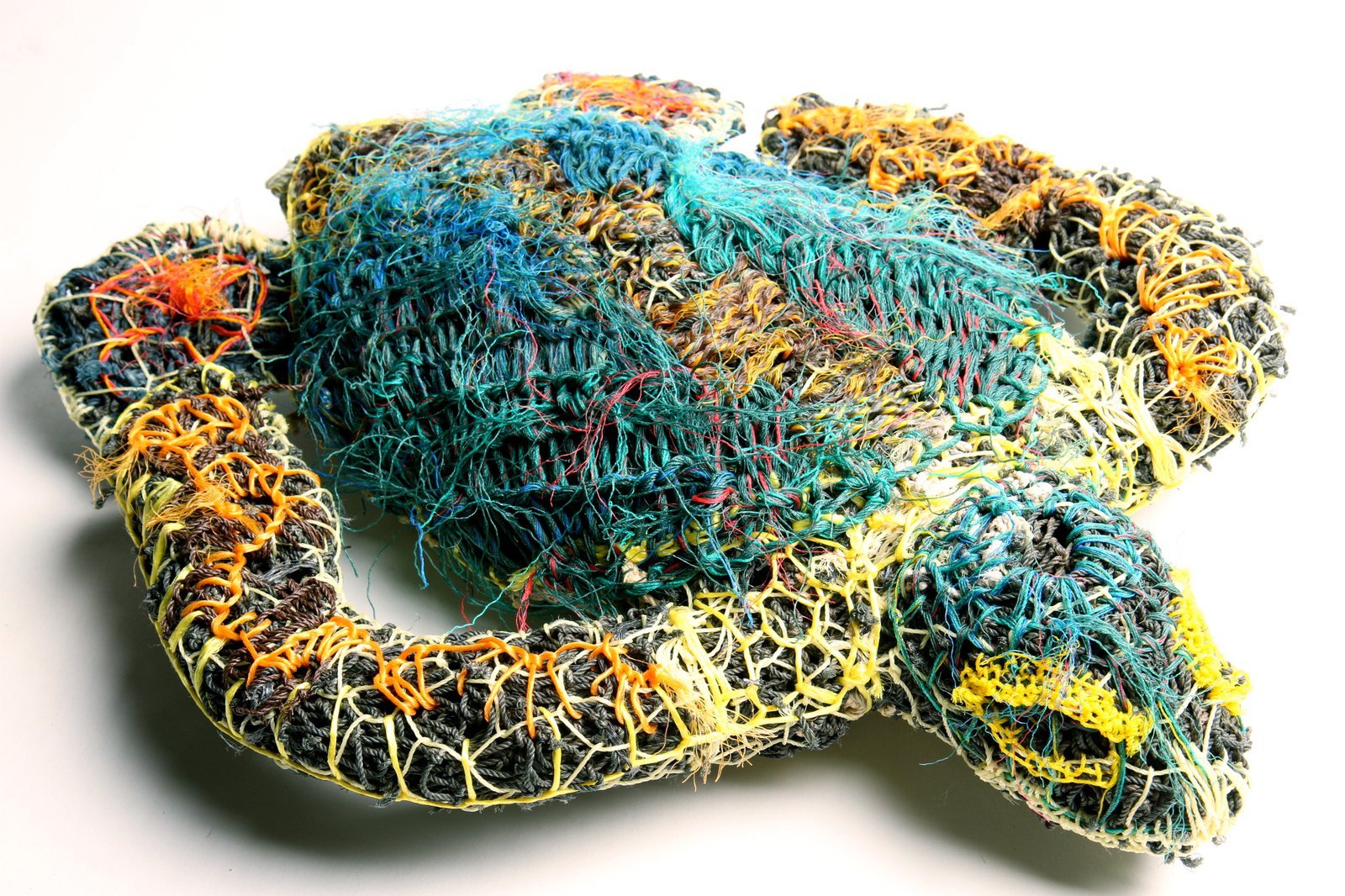

Local communities, Indigenous rangers, the Australian Navy, Parks and Wildlife Services, artists, and others contribute, at different times to retrieve ghost nets from the ocean and those buried in the sand. Responding to the wastes of industry, together they contribute to a counter infrastructure of care. Indigenous communities located in northern Australia and the Torres Strait Islands bear witness to the extractive capitalist waste damaging SeaCountry. Perhaps the best known and most creative use of derelict nets is in ghost net art, made by Indigenous communities to share stories of the sea and culture, while raising public awareness of the dangers of ghost nets. Turning destructive material into vibrant, beautiful art works is a generative practice of caring for the land and ocean. Ghost net works by Indigenous artists, sometimes made in collaboration with the Ghost Net Collective, have been commissioned and exhibited nationally and internationally.

Ghost nets are retrieved and, where they are not too degraded, re-used in a range of ways. In Northern Australia, some Indigenous communities use them to screen verandas, fence chicken pens, and make fishing and yam bags (TierraMar, 2021). At a different scale, certain manufacturing industries are also turning their attention to ways of reusing recycled fishing nets. For example, in 2025, the BMW Group plans to launch the NEUE KLASSE model of car which will feature trim parts made from 30% recycled fishing nets and ropes.

References

TierraMar, and SMaRT@UNSW. 2021. “Ghost Nets. Needs Analysis and Feasibility Study for Northern Australia, Final Report.” Sutherland, 30.

Wilcox, Chris, Grace Heathcote, Jennifer Goldberg, Riki Gunn, David Peel, and Britta Hardesty. 2014. “Understanding the Sources and Effects of Abandoned, Lost, and Discarded Fishing Gear on Marine Turtles in Northern Australia.” Conservation Biology : The Journal of the Society for Conservation Biology. 29, 1.

Image: Turtle made by Ellarose Savage in 2012 from ghost nets. Collection of the Australian Museum.

Photograph: Rebecca Fisher, Australian Museum.

https://australian.museum/learn/cultures/atsi-collection/ghost-net-art/#gallery-4