Despite more than a decade passing, the Fukushima nuclear power plant accident continues to haunt. The trajectory of the accident's flow through memory has made pain and accusations less susceptible to dilution over time. It is still imperative to tell the stories of the past so the nightmare can be reawakened in the middle of a crisis, instead of becoming a taboo topic.

On 24 August 2023, Japan launched a plan to discharge Fukushima’s nuclear wastewater into the sea. The first discharge lasted 17 days and served as a prelude to the long 30 years of discharge that followed. As the nuclear shadow seeps into the oceans, science and politics are wrapped up in a feast of different positions. In this unsettling conjuncture, we yearn for voices, stories, and more local narratives-connecting the past with a faltering future.

This article is adapted from a documentary by Chinese journalist Zhang Jun, where his camera focuses on the worrying citizens of Fukushima and allows their silenced voices to be heard.

At a fishing port in Iwaki’s Miyagi Prefecture, a notice forbidding fishermen to speak to the press (especially the Chinese and Korean media) was distributed to all fishermen.

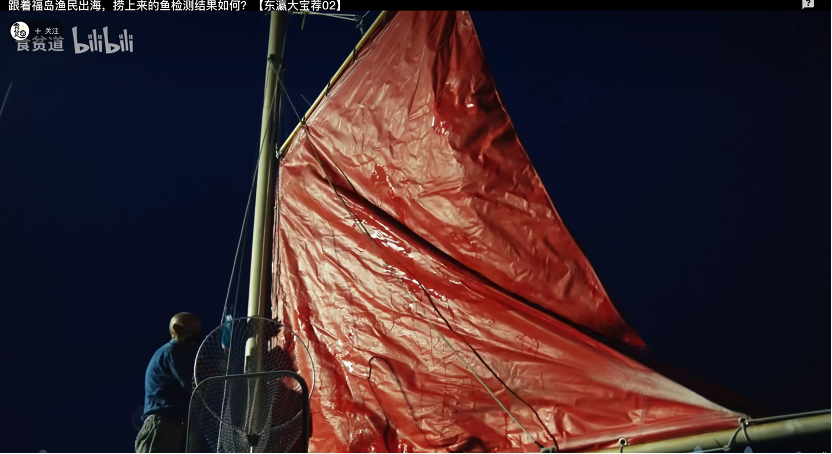

Zhang was helped by a local fisherman to go out on his boat in the name of a ‘fishing tour.’ Their destination was a fishing spot about 30 nautical miles from the nuclear power plant.

As the morning light shines, the atmosphere seems less tense than expected. In conversation with the old fisherman, Zhang learns of his last vestiges of optimism about living in such a present where drainage pipes are being laid to carry nuclear wastewater far to the east, shrugging off the visible threat to ocean currents and the future, despite its imminence.

Currently, Tokyo is committed to purifying radioactive material in nuclear effluent to regulatory levels with the ALPS treatment system before discharge. However, the state discourse does not seem to hold true in local fishermen’s knowledge. On the contrary, the frequent misappropriation of science is fuelling their scepticism.

Zhang: “Do you trust Japan’s APSL treatment system?”

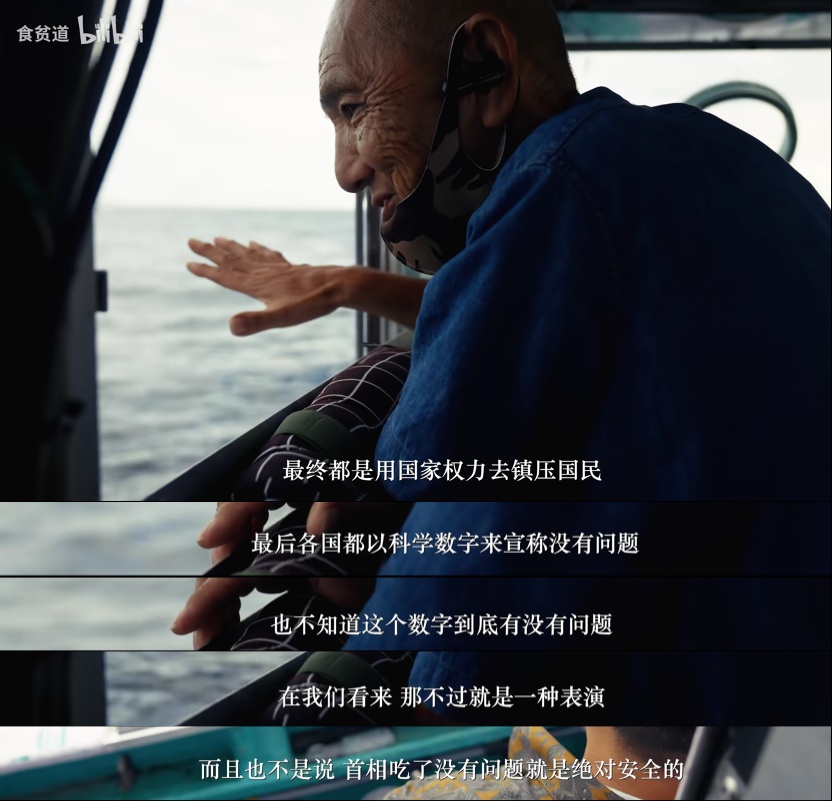

Fisherman: “I think that the view of all countries in the world is untrustworthy. After all, countries are claiming that there should be no problem according to some scientific figures. We’re not scientists, and we don’t know if there’s any problem with the figures or not. (Laughs)”

Zhang: “We read about Prime Minister Kishida tasting Fukushima seafood. What do you think about that?”

Fisherman: “From our point of view, it was just a show. And that doesn’t mean it’s safe just because the prime minister ate it. It’s not that easy.”

“Regardless of what citizens do, ultimately it’s the state power that’s being used to suppress them.”

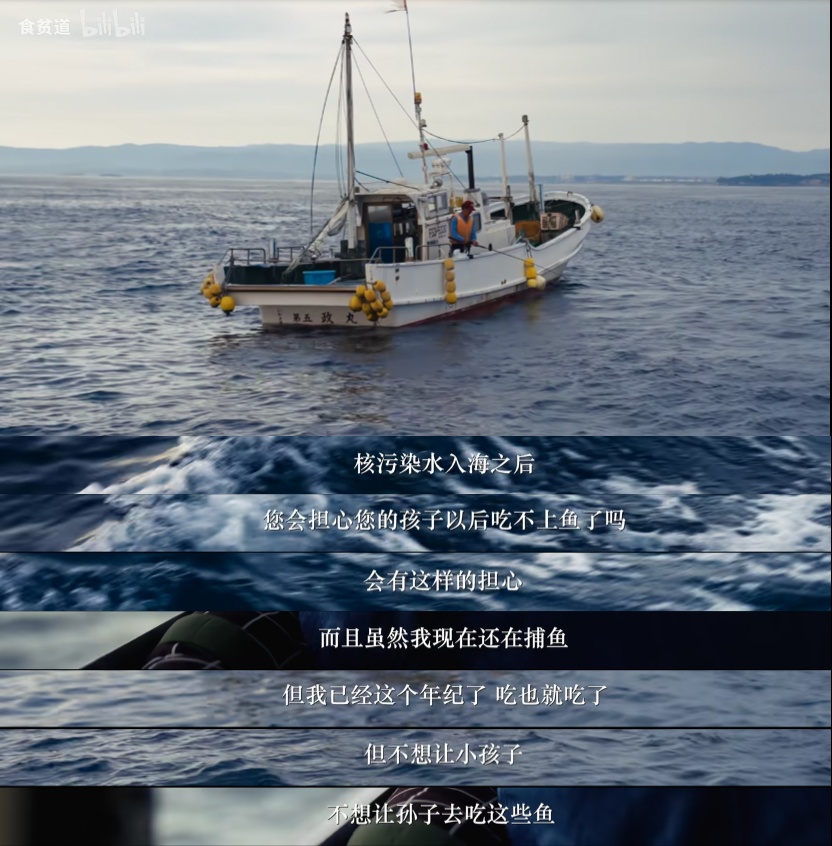

Zhang: “If nuclear-contaminated water reaches the ocean, do you fear that your children will be unable to eat fish in the future?”

Fisherman: “I would worry about that. Though I am still fishing for myself, I have grown so old that I have no fear of eating them. However, I don’t want my children—I don’t want my grandchildren—to eat all this fish.”

With a precise retrieve and the plaintive applause generated by the harvest, a small golden fish, known to fishermen as “Bellows,” is caught on the boat. Despite having escaped becoming food, this fish will end up in a Fukushima Fisheries Association testing facility.

Currently, there are only three places left in Fukushima where seafood catches can be screened for nuclear contamination. “There is no problem at all with [the fish in Fukushima] being used for food,” the inspector said, “and [the small number of remaining testing sites] is lateral proof that the safety level has been raised high.”

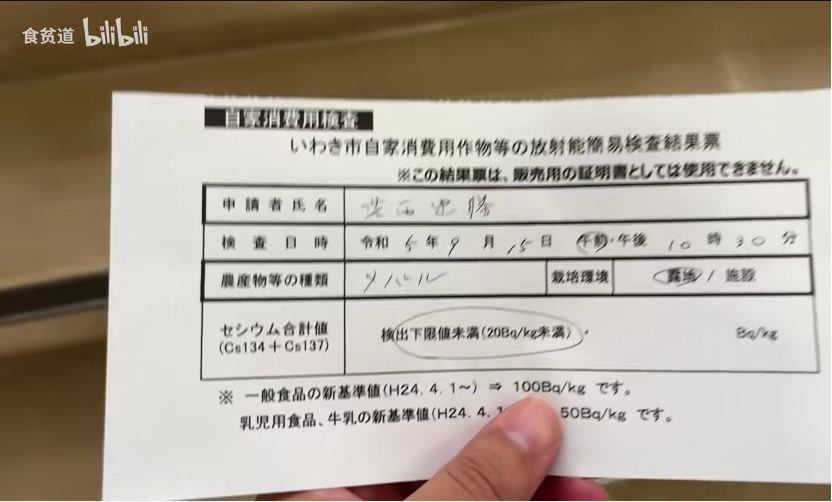

On a flimsy lab sheet is a statistic that puts Zhang and the fisherman’s worries to rest – the fish is not contaminated to the tune of 20 becquerels per kilo – a safe and edible value. But Zhang still seems to have a frown on his face, his years of investigative reporting on nuclear-contaminated areas give him a professional critical edge.

Zhang: “Since Fukushima started discharging contaminated water, there are actually three common radioactive elements besides cesium 134 and cesium 137—strontium, cobalt, and iodine. Despite not being tested here, they are high-risk and difficult to clean up with the so-called APSL instruments.”

“Even if the values are safe at the moment, that only means that on the first day, when the first wave of water has just been drained, the fish are in this (safe) condition. As radioactivity spreads through seawater, what will happen behind them? We don’t know, and they (the Japanese fishermen) themselves are uncertain.”

Original text source and illustrations

Picture sources: Screenshots extracted from https://www.bilibili.com/video/BV1sm4y1g7iM/?spm_id_from=333.337.search-card.all.click&vd_source=f5492fb7f7bb844494d1014511b065a2;

Translator: Dongyang Li