Currents carry ocean materials ‘transcorporeally’ (Alaimo, 2010) through the porous boundaries of other natureculture bodies – travelling and troubling the edges of marine park delineations, abstract jurisdictions and mining tenements.

They animate the flow of life between and through boundaries, carrying marine creatures into invisibility or the vulnerability that comes with dwelling in the spaces between. Currents insist that boundaries will be breached. They remind us of the shared or differently experienced physical vulnerabilities across human and more-than-human worlds. The relational nature of their material exchanges reminds us that bodies are always “becoming in webs of mutual implication” (Neimanis, 2013, p.25). Excess carbon molecules that move from the atmosphere into ocean waters, for example, transform the nature of the water by increasing temperature and/or acidity levels. Not only do such intra-active material exchanges have the potential to transform the materials being exchanged, but the nature of relations between bodies also transitions.

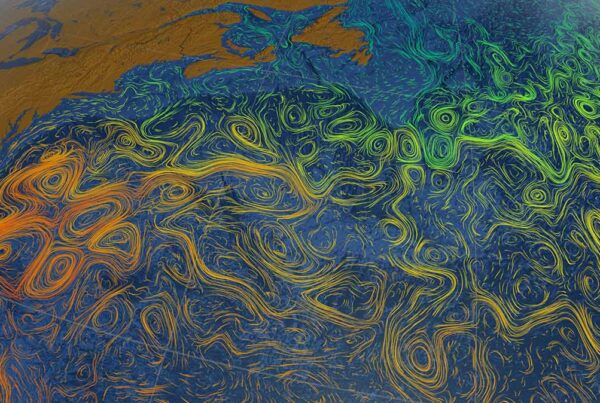

Ocean currents are exemplars, par excellence, of intra-active transitional relations. As they transition so do their relations with other bodies. For example, as the East Australian Current warms, they force some fish to migrate from familiar grounds to unknown new territories and, in the process, local relations also transition. Fishers too change their relationship to place and practices as warming currents bring new species. The temporality of different currents also forms relations with different life forms. As an example, at benthic and abyssal depths, the long slow overturning of the thermohaline provides livability conditions for slow growing vent ecologies and delicate nodule life forms. Following the thermohaline circulation to the ocean’s midnight depths is to follow an absent horizon without visibility, where the impacts of material transitions on these life forms is suspended over the long range. Thinking ecologically with the long, slow-time relations of ocean currents signals a need to place time into our considerations (Code, 2006). If relations are foundational to ethics, the transitioning, transcorporeal and intra-active relations of currents and their material solutions offer a clarion call for an ocean ethics that is attentive to potential material transitions and material memories over different temporal scales.

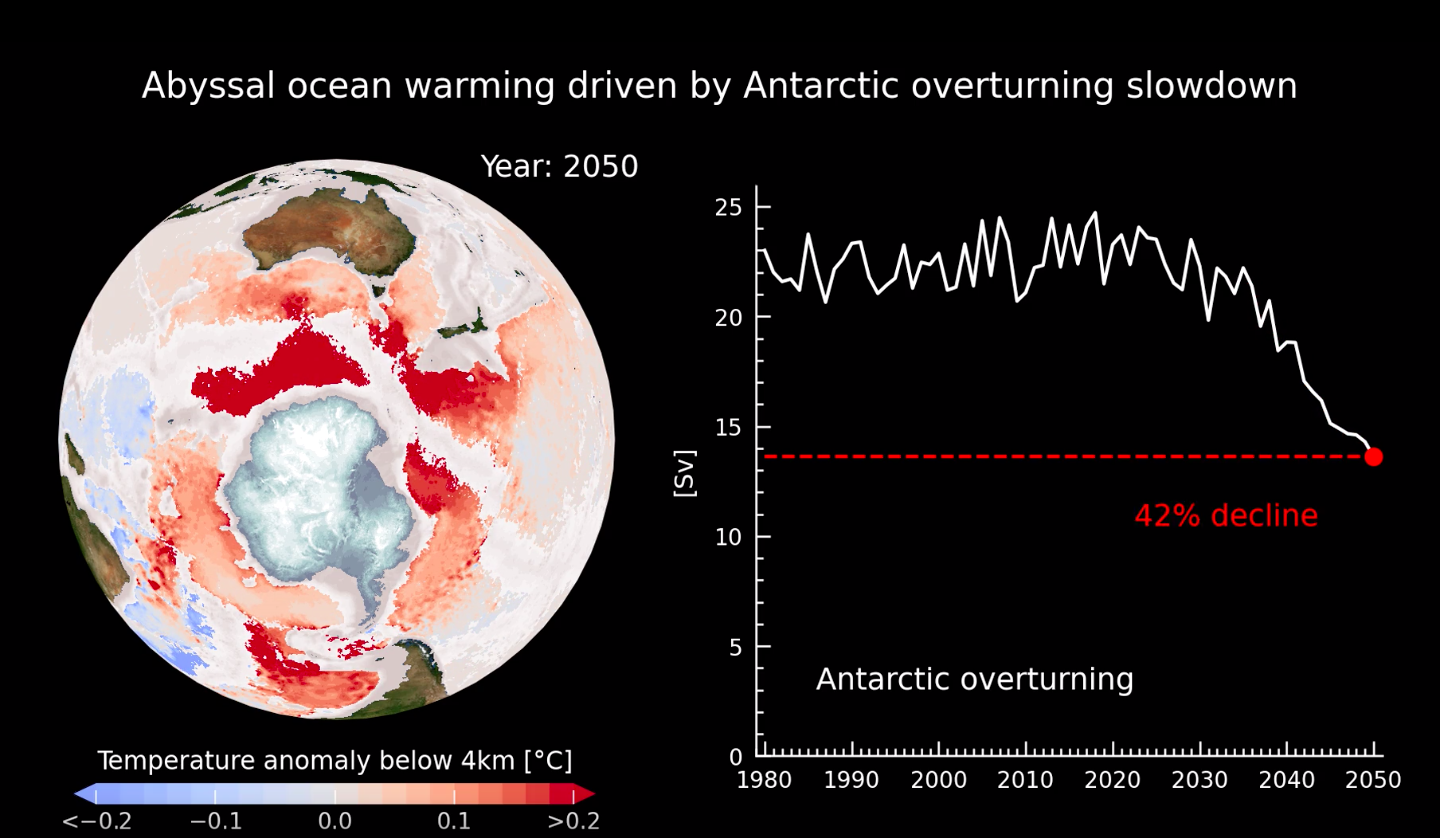

The slow passage of the thermohaline means that as warming surface temperatures deepen with our carbon streams, so the risk of long lingering warmth is cast well into the future. The climate change that we affect, and the consequent warming, transition together. Excess carbon emissions impact ocean communities through slow, longer-range and therefore less visible environmental violence that transform livability conditions. This is the ‘image weak’ meaning of slow violence described by Nixon (2011), where the slow circulation of deep ocean currents means that consequences of human actions and inputs may not appear for 5, 10 or 100 years or more into the future. Environmental impacts on the remote, deep ocean worlds are also image weak as there is little opportunity to observe changes over time.

Antarctic Circumpolar Current projections

The Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC) takes us all the way to the icy latitudes of the Southern Ocean, where they move between Antarctic research vessels, tourist boats, fishing fleets, extreme sailors and whalers. Beneath the ice and chilly dense waters, the ACC sweeps the lively ecologies of Antarctica’s broad shelf and Southern Ocean plains and ridges, gliding with communities of Weddell seals, orcas, Emperor Penguins and krill.

Gale forced by the Roaring Forties and Furious Fifties, the ACC circulates uninterrupted around the globe, connecting sea water from the Atlantic, Indian and Pacific Ocean basins. It is an eight year and 24,000-kilometre journey (Parks and Wildlife Services Tasmania, 2000). The ACC’s eastward flow pushes through the extended axis that marks the uneven and, for the most part, unrecognised territorial claims on Antarctica (Rothwell et al., 2015, p.740): first Australia, then France, Australia again, New Zealand, then eastward through a large unclaimed area before reaching the territories claimed by Chile, the United Kingdom, Argentina and Norway and then back through Australia. Surface and deep waters flow with a certainty not matched by international conservation agreements. The juridical boundaries of the UNCLOS high seas provisions and Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources marine protections are unresolved. Uncertainties associated with the conservation of marine living organisms on the Antarctic and Southern Ocean seabed combine with the region’s remote and physically difficult conditions to make enforcement of conservation regulations difficult. Unclear conservation regulations generally favour mining companies. For now, though, the steady strength of the ACC and perilous westerlies keep miners at bay, at least as long as technological fixes evade them.

Being barotropic, the ACC reaches all the way to the bottom and, as they move indiscriminately and relationally across basins, they connect seafloor to sea surface. In a passage describing the ACC’s dynamics and sensory responsiveness, Gordon (2001) describes the current’s affective ability to ‘feel’ the shape of the seafloor. As the ACC feels along the seafloor topography, the current projects their journey up into the water column, in equivalent sea surface temperature patterns. How might the watery imprints of other currents, in different locations or times, resonate through the water column? Though not yet near Antarctica’s shores, mining machinery, coral colonised drilling pylons, sunken ships, and dumped space craft already scaffold industrialised seafloor-scapes. Thinking with the ACC’s affective agency offers another way to imagine an industrial future for the polar seafloor, once favourable mineral prices, advanced technologies, corporate appetite and increasing human populations potentially embrittle the sanctity of Antarctica’s environment? How might we speculate on a watery imprint projected by a future ACC as they feel the topography of an industrialised polar seafloor? What new organisms will live in that new imprint, and which will be extinguished?

The transitional in change

Warming surface waters, storm and rain intensifications are not suddenly upon us, or separable from us, they are our natureculture transitions, carrying all the way along the intensifying activity of industry and increasing emissions to the warming ocean. François Jullien (2011) observes that transitions are not easily discerned, often invisible, and unspoken except in the eventual signalling of transformation that they bring about. The slowing thermohaline circulation and increasing presence of plastics are just visible outcrops of subtle transitions already underway.

Transitions are not all imbricated, as if some earlier ocean conditions might return once prevailing conditions are removed. Some transitions signal irrevocable transformation. We talk of changing currents, changing climates or the changing ocean, as if the currents, climate and ocean possessed some form of prior integrity, rather than a continual transition. Cutting through change to transition enables certain relational connections between bodies to be more closely understood. As a processual quality, for example, transition is shared across nature/culture, humans and more-than-human.

The ocean’s transitions are silent transformations that are not easily seen and for which there are no utterances yet shaped to respond. The ocean’s silent transformations may be either too far away, unfolding over the long range of the thermohaline, or more contemporaneously, through the extending warm streams of the EAC; or the gradual removal of ocean pulses too small to see. Missing the silent material transitions of our material inputs and extractions we are, as Jullien (2011) observes, surprised or bewildered when the visible effects appear.

See also: Transitioning currents in times of climate change – Part One

Adapted from: Reid, S. (2018). “Transitioning Currents in Times of Climate Change.” In Living with the Sea, 114–28. London: Routledge.

References

Alaimo, S. (2010). Bodily Natures: Science, Environment and the Material Self. Indiana, USA: Indiana University Press.

Code, L. (2006). Ecological Thinking; The Politics of Epistemic Location. New York: Oxford University Press.

Gordon, A. L. (2001) Current systems in the Southern Ocean. In Encyclopedia of Ocean Sciences. Oxford: Academic Press, pp. 613‒621. [Online] https://www.sciencedirect. com/science/article/pii/B012227430X00369X (Accessed 30 May 2018)

Jullien, F. (2011). The Silent Transformations. London: Seagull Books.

Neimanis, A. (2013). Feminist subjectivity, watered. Feminist Review, 103, 23–41.

Nixon, R. (2011). Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Parks and Wildlife Services Tasmania. (2000). Antarctic Circumpolar Current. Hobart, Tasmania: Parks and Wildlife Services.

Rothwell, D., Elferink, O., Scott, K. and Stephens, T. (Eds). (2015). The Oxford Handbook of The Law of The Sea. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sanderson, K. (2008). Krill spotted diving at depth. Nature.

Video: Abyssal ocean warming driven by Antarctic overturning slowdown

Credit: “A Critical Ocean Current Has Scientists Talking about The Day After Tomorrow.” The Sydney Morning Herald. March 29, 2023.

https://www.smh.com.au/interactive/hub/media/video-loop/15336/TEMP_4km_Anom_LANDSCAPE.mp4

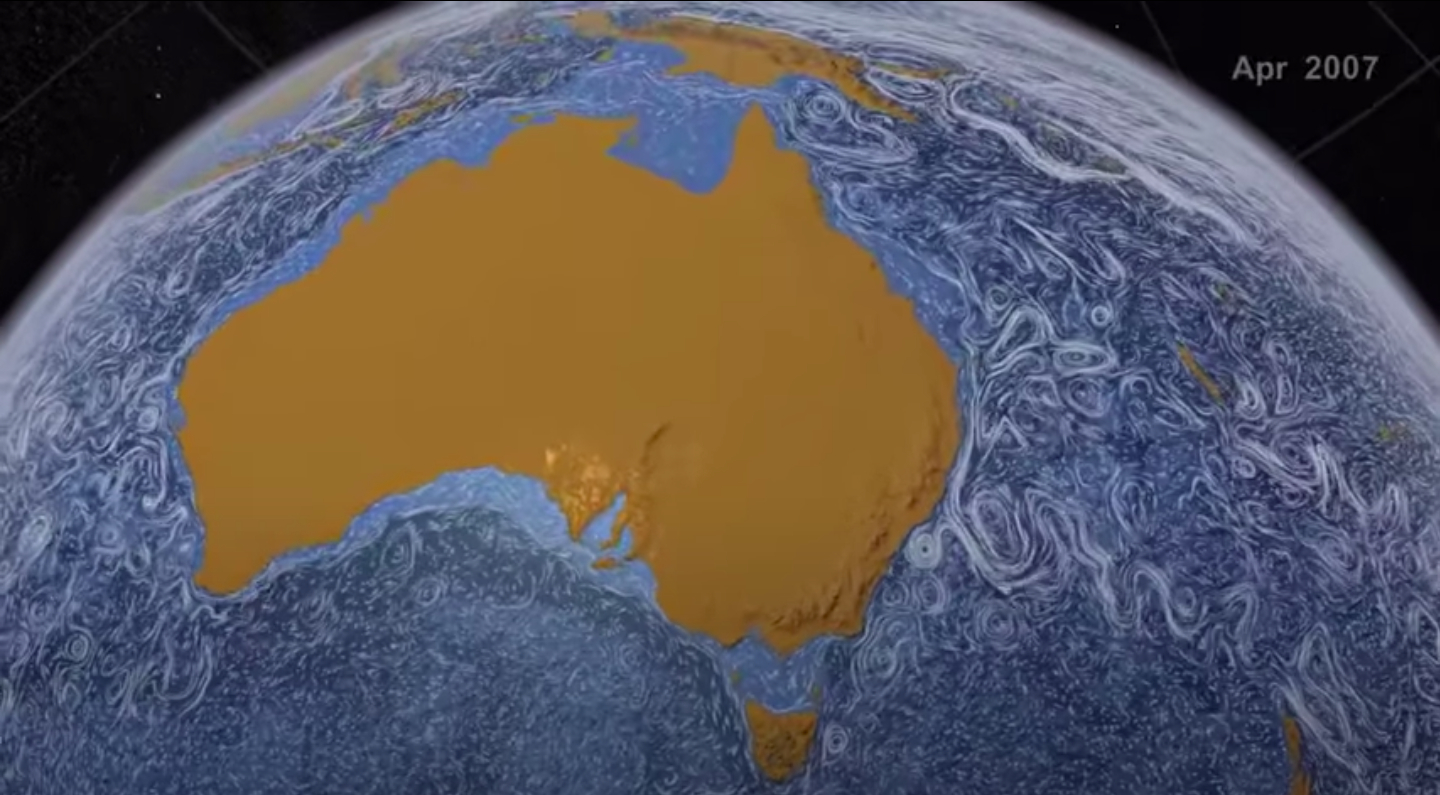

Video: NASA | Perpetual Ocean