Extraction as a concept and a set of practices is far from being an isolated phenomenon. It is tied in with an enabling set of ideas, most notably to those associated with liberalism: the freedom to accumulate wealth, freedom of the individual, the freedom to exploit the Earth’s resources, and the idea that once accessed, these resources flow ‘for free.’

The Browse basin off the North-West coast of Western Australia is an ancient undersea reservoir of methane that is the start of a production line providing energy to burn for economic growth. Burning methane releases carbon dioxide as a by-product (CH4 + 2O2 ––> 2H2O + CO2 + 890KJ); but this CO2 is not released ‘for free’ into the atmosphere because there are costs: the known greenhouse effects. Extraction logic does not take this cost into account, since it sees pure freedom at both ends of the production line, the freedom to extract and the freedom to emit. The focus is more on the accumulating wealth, which is carefully accounted for.

Woodside Energy is the main actor in the gas extraction business in this part of the world. At the moment their gas is being processed on off-shore platforms and in Karratha. Further north from there, near Broome, a concerted campaign by the Indigenous Goolarabooloo community and an alliance of conservation and green organisations halted a Woodside-led plan to build a huge processing plan on the beautiful coastline at Walmadany (James Price Point) in 2103 (Muecke & Roe, 2020). Meanwhile, today, exploratory fracking proceeds apace in the hinterland, as this remote part of Australia is treated as a frontier that is ripe for heavy industry.[1] Since this is happening on Country that has only been colonised since the 1890s, we can speak of this kind of industrialisation as an arm of extraction colonialism (Norman, 2016). Settler colonialism is quite different, it is the building of infrastructure for people to live on the colonised lands. In the North-West, the Kimberley, settler colonialism has morphed into extraction colonialism, the proof being that today’s emblematic worker is FIFO (Fly-In, Fly-Out).

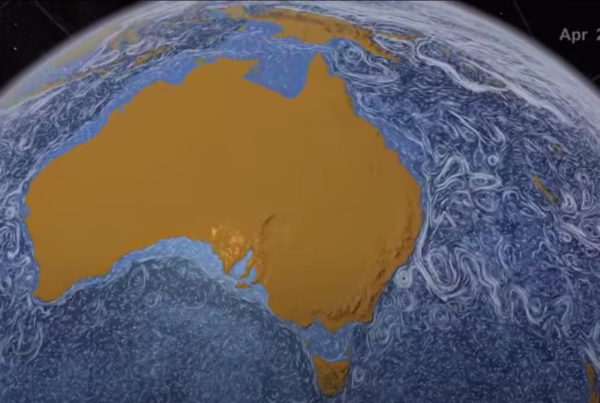

Figure 1: A seaside LNG plant

There is no doubt that this case is but one example of an extractive industry pursuing a (neo-) liberal capitalist dream. Of course, there are opposing ideas, which critics of this kind of industry are interested in developing for great effectivity. But the ideas that were set up in opposition to it by the green consortium, were, as Bruno Latour put it, possibly not ‘thorough enough’ in their critique:

I have a weakness for thinking that the ideological work being done by Green parties is not thorough enough. A lot of time and effort were needed to create the fiction of the rational individualist Man, homo economicus, on which the economisation of the world is based. They had to invent everything, redefine what liberty and abundance meant, spread around imaginary ideas, value systems, descriptions of the world. Ecologists have yet to do this work. They thought it wasn’t necessary to deal with these questions; that it was enough to talk about ‘nature’ and how to protect it. (Latour in Lemonnier & Noyon, 2022; author’s translation)

Figure 3: Walmadany (James Price Point)

With ‘liberty and abundance’ Latour was referring directly to his more junior colleague, Pierre Charbonnier, and his Affluence and freedom: An Environmental History of Political Ideas (originally Abondance et Liberté, 2020). So, when we talk about extraction in the context of political ecology, as a rather negative concept that should be critically investigated, we can’t simply extract it from its own conceptual ecology! We have to rethink it along with the many other concepts that enable it; we have to be more ‘thorough’.

Extraction, it seems to me, is only extraction if it is a movement across a power asymmetry, across some kind of border. If someone harvests vegetables from their own English village garden, there is no ‘extraction’; the flow is internal to an autonomous domestic economy where they enjoy their freedom. ‘Autonomy’, or political freedom, consists, in Charbonnier’s book, ‘in forming a political community transparent to itself, which determines its laws and orientation according to this knowledge, to this representation…the liberation of individuals ensues’ (p.89–90). The very definition of liberalism is forged in this real or imagined community. But at the same time, its economic growth is determined by and from an external territory where its citizens do not live, from ‘ghost acreage’ in Pomeranz’s formulation [2]. ‘Its “extractive” character’ [Charbonnier goes on to say] ‘is characterized by a growing gap between this project and the conditions in which it manages to be realized: as soon as access to new productive processes and inexpensive and abundant energy sources, combined with violent appropriation of land and labour placed under colonial authority, becomes a determining factor in the pursuit of the project of autonomy, any conception that does not take these geo-ecological conditions seriously is ruled out of court’ (p.90). I think he means that they think their liberty is self-determined, but it isn’t. It comes only by way of breaking their own laws somewhere else, through illiberal behaviour.

Yet they think liberalism is their greatest virtue. It is the last value they will give up in any negotiation: their freedom to prosper, their freedom to own territory, their freedom to extract materials that the Earth seemingly gives up ‘for free’. In his discussion of Tocqueville’s Democracy in America, Charbonnier sees that newly autonomous nation, at the time, as emblematic of the future definition of liberal democracy, founded on the principles of prosperity, equality and private property. “No prosperity without property and market—is this the official doctrine of liberalism? The unofficial doctrine [the ‘well-kept secret’] suggests the opposite: it is the extensive exploitation of natural resources that makes possible the genesis of an egalitarian society.” Tocqueville had noted this, but downplayed it: America had ‘providence,’ natural endowments. It would be “a boundless continent, which is open to their exertions” (p.91).

Charbonnier’s thesis is that it is not so much societies that invent their political ideals and put them into practice, but rather it is the material ecological conditions surrounding them that make these political ideals possible. He is indeed saying that these concepts we cherish, democracy, freedom, etc, have only been made possible through constantly finding ways to increase productivity, and this includes colonisation or expropriation of American Indian or Aboriginal lands. Any specific ‘correction’ is difficult, because all the concepts shift at once. One cannot say, for instance, ‘stop exploiting those lands, those peoples’—and extract the concept of extraction—and maybe ‘let them join in and have their fair share of the spoils,’ because a runaway structural logic is in place. Something else, or someone else, will end up being exploited.

But on the frontier, in the Kimberley where extractivism is not as advanced as much as in the heavily industrialised Pilbara a bit further south, the contrast with Indigenous modes of existence is exceptionally stark. Indigenous people are inhabiting their ancestral territories, but the mining industries are treating these territories as fields of extraction, and destructive effects are immediately visible. It goes without saying that the wealth accumulates elsewhere, shoring up shareholders’ freedom to live as they please.

It is opposed, typically, by a protectionist story that is hampered by sharing some of the same fundamental concepts, for instance the concept of Nature. Nature, for productivists, is stuff that is always there to be ‘improved,’ value-added, while for protectionists it is treated as ‘pristine’ and unnegotiable. In both cases, the relationship between humans and nature is asymmetrical, across that infamous nature-culture divide. It is as if humans have no firm connections with the ecologies that sustain them, no comings and goings, just treating other forms of life as external and passive.

The kind of protectionism I have characterised here is ‘conservative’. It sees the Country as finite natural capital, but I glean from Charbonnier that another kind of protectionism is possible: a socialist protectionism would see the Country as valuable for its ongoing actions: for instance, wet-season flooding flushing the river valley making seasonal species thrive, etc. ‘The political ideal of autonomy,’ says Charbonnier in relation to the political vision of Hobbes and Locke, ‘ could be achieved only once the problem of the relation of humans to the outside world had been settled’ but ‘socialist reflection [kept alive by Polyani] has sought to establish itself in a conceptual space which retains all its problematic character vis-à-vis the forms of subsistence, and more generally with the modes of collective relation to the world’ (p.158, his emphasis).

Colonial relationships are of course asymmetrical according to a number of dimensions, including flows and accumulations wealth and knowledge, but so too are extractivist relations, which no longer map onto racial/colonial asymmetries. As Anne Poelina, Chair of the Martuwarra [Fitzroy River] Council, has noted: ‘multinational corporations are the new colonisers’ and ‘it is not a black or white question any longer.’

Figure 2: Martuwarra (Fitzroy) River

Introducing or reintroducing symmetries is a counter-extractivist strategy. The work of the Indigenous bodies like Martuwarra Council, driven by Anne Poelina, is doing everything it can to put Indigenous knowledges and protocols in place, that is, between the productivity machinery and the actual Country. Mediations that are more symmetrical than the one-sided practice of ‘going in, taking it, and getting away with it.’ When, for instance, a mining company has to negotiate with an Aboriginal community to get permission, or the more abstract ‘social licence.’

How does one negotiate with these seemingly incommensurate knowledge systems? One way, dominated by a secular positivism, is to either ignore the existence of figures like Yoongooroogoo the Rainbow Serpent, a creation being, or condescendingly concede that there is a ‘belief’ that has to be ‘respected.’ And ignore it anyway. Another is to be much more self-reflective and symmetrical in exchanges of knowledge. When asked about the Serpent (as in: “Hey, Joe, what’s all this about a Rainbow Serpent?”) a Nyikina person might try to assert symmetrical reflection:

“It’s something really sacred, like Christmas is for you mob.”

“But I don’t believe in Christmas.”

“Maybe, but every year you still respect it.”

That exchange sets thinking going in a direction that is non-reductive, as in, not everything can be reduced to secular positivist thinking, or to the economy. It sets thinking going in a direction where different life forms, and their worlds, are worthy of more meaningful ‘respect’. But how does that play out, in practice?

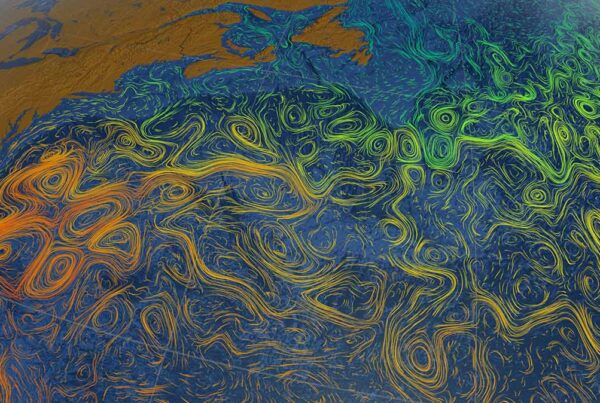

The Serpent/river’s ‘right to life and to flow’ can be backed up by ecological studies about the importance of ‘flow.’ That is, the ways that the river provides ongoing, long-term ‘ecological services,’ what Charbonnier calls ‘non-produced conditions of human subsistence’ (223). These might include the ways in which soils or molluscs filter water to keep it clean and potable. Charbonnier’s anti-productivism stresses sustainable and sustaining long-term ‘services’ that don’t manufacture anything at all, least of all money.

And water can be turned into a product by way of accumulation; packaged and commodified according to the old property values of classical and neo-liberalism (Harvey, 2005) [3]. If it is not to be produced and accumulated, it can remain a flow, constantly delivering essential ecological services. But these, to be given their true values, have to be described. And at this stage we often just theorise flows, as in Deborah Bird Rose (2022):

…everything, at pretty well every scale, depends on others through flows of energy and information.[4] Flows brings us directly into thinking with mutualisms—giving and receiving—and into exchanges that work across human and non-human domains and kingdoms. Many of the flows of energy and information bring forth and sustain life. Necessarily as well as beautifully, they are always in motion. (p.13)

I started by looking at extractivism in the context of the classical liberal framework that sustains it. I then argued that its critique had to be more thorough in the sense that it had to be a critique of the whole network. Extractivism, which now from time to time focusses on the waters of the Martuwarra, operates within the common sense of a dominant system. Extraction is discovered through geological knowledge, protected by laws, spruiked by politicians, enabled by financial devices, and sustained by the ‘fiction of the rational individualist Man, homo economicus’ (as Latour said), among other fictions like the myth of progress and the fantasy of future prosperity for all.

This liberal world is still functioning and intact, but it is founded on an original and ongoing injustice that the colonised peoples of Australia will never forget: it is their territories that produce this prosperity within a liberal system, their Countries being exploited and destroyed. The flow goes one way, accumulating elsewhere.

This world may be functioning, but large cracks are appearing. We saw these open up when Woodside was stopped from building a huge LNG plant on the Kimberley coast in 2013, after a five year battle. This was the most successful Indigenous/Green alliance against industrialisation in Australia’s history. How did it work? Will it work again to keep the Martuwarra flowing? There are new elements that can be used to recompose the old liberal political system. They are not elements that we can just introduce at will, as if we had the power. They are existing environmental conditions that can enable a new kind of politics: the power of mythological beings from the Dreaming that remind us that ‘pluriverses’ (cultures) matter. The twilight of the industrial productivist paradigm. Ecologists’ descriptions of long-term ecological services that sustain the lives of humans and non-humans. The revival of socialist thought, the ‘new ecological class’, that retains the idea of collective responses to matters of common concern (Latour & Schultz, 2023). Philosophies of flow rather than accumulation. Or am I dreaming?

Footnotes

[1] For example, Kimberley Mineral Sands (Thunderbird Operations) is now mining near Broome.

[2] Kenneth Pomeranz argues in The Great Divergence (2001), that British industrial development was predicated on the resources contributed by distant “ghost acres” of land inside the British Empire and beyond.

[3] David Harvey explains Marx’s primitive accumulation as a process which principally “entailed taking land, say, enclosing it, and expelling a resident population to create a landless proletariat, and then releasing the land into the privatised mainstream of capital accumulation”

[4] Deborah Bird Rose’s footnote: J. V. Ward and Jack A. Stanford, ‘Ecological Connectivity in Alluvial River Ecosystems and its Disruption by Flow Regulation’, Regulated Rivers: Research and Management 11, no. 1 (1995).

References

Bird Rose, D. (2022). Shimmer. Edinburgh University Press.

Harvey, D. (2005). “ch. 4 Accumulation by Dispossession“. The New Imperialism. Oxford University Press.

Latour, B. and Schultz, N. (2023) Memo on the New Ecological Class, London: Polity.

Lemonnier, M. & Noyon, R. (2022). “Bruno Latour : ‘Le programme de M. Macron avait un sens en 1945!’” L’Obs, 7 January 2022.

Muecke, S & Roe, P. (2020). The Children’s Country: The Creation of a Goolarabooloo Future in North-West Australia, Rowman and Littlefield International, London.

Norman, H. (2016). ‘Coal Mining and Coal Seam Gas on Gomeroi country: Sacred lands, economic futures and shifting alliances’, Energy Policy, Volume 99, 2016, pp. 242-251