The exploitation phase of the deep sea mining regime is looming into reality with resource corporations keen to extract mineral rich polymetallic nodules from the Clarion Clipperton Zone in the north Pacific.

The area is already carved up into potential lease areas for exploitation that will be overseen by the International Seabed Authority (ISA).

Under the United Nations Convention on Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), ‘resources’ are defined as ‘solid, liquid or gaseous mineral resources in situ in the Area at or beneath the seabed, including polymetallic nodules’ (Part XI, Article 133a). Under the ISA’s Draft Regulations for Exploitation of Minerals, polymetallic nodules are defined as “any deposit or accretion of nodules, on or below the surface of the deep seabed, which contain metals.”[1] In other words, nodules are identified exclusively by their constituent minerals.

The broad/vague definitions deployed through the soon to be finalised regulations of the ISA’s Mining Code and UNCLOS serve to assimilate multibeing, mineral assemblages, such as nodules, into extractive regimes of value. They say nothing about material relations or life worlds connected to the nodule assemblages —the multiplicity of other materials and living communities with which they are co-constituted having been bracketed out.

How might we respond to this denial of the ocean’s agency and multibeing relations? My approach is to read between the law and marine scientific material to read the ocean back into the law, or what I term seatruthing. ‘Seatruthing’ reveals that the seafloor, sediments, and nodules ought to be acknowledged as “more-than” worlds that exceed their appropriation into UNCLOS’s extractivist regime of value. The Area is more than a seabed jurisdiction for the extraction of minerals. In this sense, “mineral” too can be better recognized as more-than-mineral and in diverse kinship connection across the sea- bed.

The seafloor is not inanimate. Neither is the sediment, which is targeted for mining, a heterogeneous or inert substance. They have agency and are alive with material relations, providing nurturing ooze for the eggs and larvae of deep-living beings and affording conditions of livability for free-swimming adults.

Thinking with the entangled relations of seabed sediments, water column, nodule assemblages, and others, reveals just how inalienable they are from their constituent minerals. The formation and material relations of nodules exceed their extractivist representations as inanimate, potato-shaped rocks and fungible units rich in mineral wealth. Nodules are lifeways in progress in the deep time of abyssal worlds. They are indivisible from the sediments on which they rest and the watery atmosphere of the ocean through which their materiality slowly layers into being.

Defying the pressure from several kilometers of watery atmosphere above, the yielding ooze below, and their incredibly slow formation, mysteriously the nodules remain at the sediment surface.

It is precisely because of these lively, multibeing seabed relations that nodules assemblages situated on abyssal plains, can stay above the surface for millions of years. As Dutkiewicz and co-authors note, the reason they don’t get covered by cumulations of falling particles or sink into the soft sediment is because “starfish, octopods and molluscs are foraging, burrowing and ingesting sediment on and around them” (Dutkiewicz et al, 2020).

Ironically, it is the agency of multibeing communities that maintains nodule fields in a way that makes the nodules commercially viable for extraction.

The mineral kinship shared with nodule assemblages, xenophyophores, octopuses and other multibeing lives and lifeways, blurs distinctions between what could reasonably be understood as non-living or living resources for the purposes of the international law, extractive regimes, and our own reliance on mineral provisioning. Against the law’s oversimplifications, nodule, and other such assemblages, are more than minerals in that they are also variously hold fasts, base camps, creches, refuges, orientation points, and echolocation or sound reflectors. Foregrounding these multibeing kinships reminds us that the manganese, copper, and lithium that constitute batteries, household wiring, and computers all come to us with their watery worlds. A whole lot of lives and lifeways must be extinguished to extract minerals from ores, sediment, and nodule assemblages.

The law’s aversion to recognising multibeing relations and conditions of material embodiment and vulnerability, surface in both the seabed mining regulations and the seabed mining regime’s common heritage of mankind principle.

However, there’s nothing in the convention that explicitly defines this principle. So how else might it be re-imagined through less extractive, and more relational, multibeing terms? Could one imagine, for example: the common heritage concept of ‘allkind’? Here are other suggestions:

- The common heritage concept of ‘allkind’

- A principle concerned not with the profits to be reaped by corporations from destroying seabed communities but rather the multibeing connection that we all share with the ocean as materially embodied beings.

- A concept that encompasses our interdependent biological, mineral, chemical, watery, and sonic relationships with the ocean.

- Where the ‘common heritage’ of the seabed acknowledges how the seabed is ‘indispensable to human life’ (Hunter et al, 2018)

- Could CHM’s inherent entitlement to take from the ocean, be balanced with an obligation to give back, to paraphrase Val Plumwood (2002). What does or would giving back to the ocean, look like?

- Thinking with Lauren Berlant’s explorations of infrastructure and infrastructural analysis, could CHM be animated as a provisional, relational infrastructure, adaptive to the planet’s transitioning multibeing conditions, and in particular, likely intensifying human material needs and changing ocean conditions? (Berlant, 2022)

- Rather than presuming a common heritage, how might the individual elements be re-conceived– for example, imagining the ‘common’ in the CHM as a verb, an action concept, an exceptional predator’s responsibility for care, a tactic for ensuring world-making possibilities amidst inalienable violences.

- The intertemporal dimensions of the common heritage of mankind principle casts anthropocentricism as a hereditable condition that is to define our dominant relationship with the deep ocean well into the future. How can we think of this differently?

- CHM’s ‘heritage’ element presupposes future generations as if the ocean’s material conditions are fixed, or as concepts of what it means to be human are also unchanging or equate only with corporate humanity. How might the CHM concept reimagine futurity?

- Bringing ocean agency into legibility is also critical to reimagining relational, multibeing concepts of common heritage. How can ocean agency be understood more expansively?

[1] Schedule: Use of terms and scope, Draft regulations on exploitation of mineral resources in the Area, ISBA/25/C/WP.1.

References

Berlant, Lauren. 2022. On the Inconvenience of Other People. Writing Matters! Durham: Duke University Press, 314. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781478023050

Dutkiewicz, Adriana, Alexander Judge, and R. Dietmar Müller. 2020. “Environmental Predictors of Deep-Sea Polymetallic Nodule Occurrence in the Global Ocean.” Geology 48 (3): 293–97. https://doi.org/10.1130/G46836.1

Hunter, Julie, Pradeep Singh, and Julian Arguon. 2018. “Broadening Common Heritage: Addressing Gaps in the Deep-Sea Mining Regulatory Regime.” Harvard Environmental Law Review, April. https://harvardelr.com/2018/04/16/broadening-common-heritage/

Plumwood, Val. 2002. Environmental Culture: The Ecological Crisis of Reason. London: Routledge.

UNCLOS Part XI, Article 133(a).

Image: Manganese nodule as a breeding ground for octopuses.

Credit: Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute and the University of Hawaiʻi

https://www.soest.hawaii.edu/soestwp/announce/press-releases/manganese-nodules-as-breeding-ground-for-deep-sea-octopods-2/

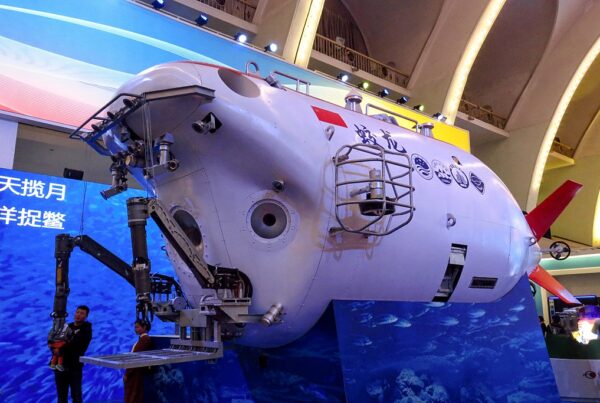

Image: Composite of deep seabed mining machines

Credit: Susan Reid