The ocean is more than a life realm, the sum of species biodiversity, a vibrant phenomenon, space or fluid.

Their local and planetary uniqueness is determined by the physical materiality of watery solutions,

planetary forces,

diverse pluri-multi-poly marine constituencies,

sonics,

dynamic systems,

human waste and extractions,

and the relationality of all these elements.

Multibeing

My concept of ‘multibeing’ acknowledges the material, social, and temporal dimensions of ocean life and lifeways–a recognition of the ocean’s agency and relational milieu beyond narrow species categories. It takes into account conditions of material embodiment and vulnerability across allkinds, lifeworlds and ways (Reid, 2023). For the growing human populations on this planet, our need to provision materials (albeit differently) implicates us all as exceptional predators.

The ocean’s governance regime fails to recognise these agentic and multibeing dimensions of the seas. In relation to the seabed, the United Nations Convention on Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) mandates the International Seabed Authority (ISA) to manage activities in the international zone, known as the Area– a jurisdiction that encompasses over 40 percent of the earth’s surface, or 57 percent of the total area of the earth’s ocean. Under this regime, the deep ocean and their seabed are re-conceived and portrayed as lease areas and quarry realms—abstracted zones of mineral and non-agentic, biological matter ready for extraction.

The ISA is finalising a Mining Code that, once completed, will allow it to approve exploitation licenses for individual mining lease areas of up to 75,000 square kilometres in size. The target site for the commencement of deep seabed mining is known as the Clarion Clipperton Zone (CCZ) in the north Pacific–an abyssal site rich in commercially valuable minerals deemed by corporations and economists to be ‘critical’ to the world’s ‘green’ transition. If all current mining interests in this area were to be realised, ‘it would be the largest contiguous mining operation’ on the planet (Coumans cited in Brabaw, 2023). Significantly, this is also an abyssal habitat of ecologically precarious marine beings and lifeways not well understood by marine sciences. Mining would destroy these, including life forms that took millennia to come into being.

The common heritage of mankind principle is UNCLOS’s signature and justificatory tool for the exploitation of the international seabed (Article 136). Under the principle, property rights in the mineral resources of the Area are vested in ‘mankind as a whole’ and the ISA is to manage these resources also on behalf of ‘mankind as a whole.’ The principle economises these benefits and claims to speak on behalf of all of humanity. In reality, it is part of an exploitation architecture that includes UNCLOS, the ISA, the soon to be finished Mining Code, and the operationalisation of this regime that privileges extractive corporations.

If it is accepted that humans are materially embodied, reliant on the ocean for wellbeing, and ecologically interconnected with other-than-human marine communities and lifeways, how could the excessive, environmental violences that will result from multidecadal commercial seabed mining activity benefit humanity “as a whole”?

UNCLOS’s wider environmental protection provisions extend the application of CHM to protection and preservation of the marine environment (UNCLOS Preamble, paragraph 5; UNCLOS Article 145 (a), (b)). However, these protections appear subjugated when read alongside the Convention’s dominant economic development goals and taking into consideration the ISA’s operational biases and foundational mandate as a miner– via the Enterprise [1].

Notes

[1] UNCLOS Preamble paras 5, 6 and 7; and Article 150 provide that activities in the Area ‘be carried out in such a manner as to foster healthy development of the world economy and balanced growth of international trade, and to promote international cooperation for the over-all development of all countries, especially developing States’. Once operational, the Enterprise will be the third actor at the seabed along with corporations and States, (UNCLOS Art 170, The Enterprise).

References

Brabaw, Kasandra. 2023. “Canadian Company in Race to Mine Seabed, Unperturbed by Ottawa’s Ban on Seabed Mining.” February 19, 2023. https://famousbio.net/news/canadian-company-in-race-to-mine-seabed-unperturbed-by-ottawas-ban-on-seabed-mining/.

Reid, Susan. 2023. “Ocean Justice: Reckoning with Material Vulnerability.” Cultural Politics 19 (1): 107–27. https://doi.org/10.1215/17432197-10232516.

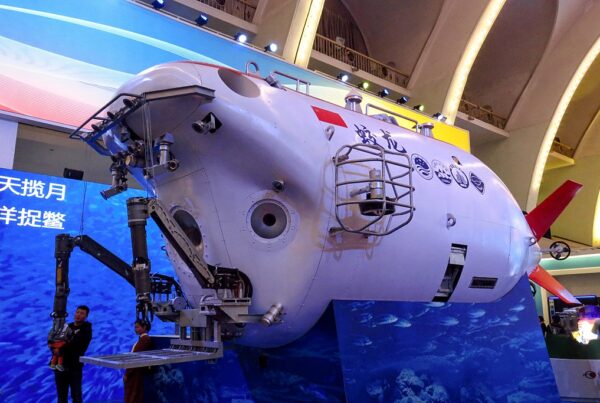

Image: Xenophyophores and other seabed lifeways. Courtesy of NOAA