Aberdeen, Scotland is known as the Granite City for its austere grey buildings. When the sun shines (rarely), they sparkle. Mainly it doesn’t and they don’t.

The raison d’être for Aberdeen is the North Sea which adds an immense backdrop of grey. Lovely Doric words capture its climatic influence: dreich (bleak, wet) rendered even more so when a haar rolls in (a frequent sea fog).

Figure 1: Aberdeen beach.

The North Sea divides the city economically, socially and culturally. There is no better place to understand this than at the Aberdeen Maritime Museum. Over the twenty-plus years my partner and I faithfully visited her parents and family in Aberdeen I spent a lot of time in the Museum. I went to escape, to do research on fishing, and also because for me it caught the sociological – if not any other – fascination of the Granite City.

Figure 2: Aberdeen Maritime Museum

As you walk into the round edifice, you encounter a large model in the middle atrium which divides the three floors: to your left, it tells the history of fishing and the fishing industry for which Aberdeen was renowned; to your right is the tale of offshore oil and gas exploration. A memorial to fishing guards the outside (Figure 3). It was only – and belatedly – opened in June 2018. According to newspaper reports, it was important for many to remember the old days and former friends and family. As a former trawlerman from Boddam said “It was a very emotional moment for me and the trawlermen that are left. It’s been a long time coming but at least we now have a focal point where people can come and reflect. This is the closest a lot of people will get to having a gravestone, as their bodies were lost at sea.” (in Wyllie, 2018)

Figure 3: Aberdeen Fishing Memorial

Fishing and the fishing industry were central to North Eastern Scotland for centuries going back to the Norsemen in the 9th century. It was only in the 19th century that it became a fully industrial affair. The rules and cultures were complex, involving class, gender, and regionalism. I’ve written on Scottish fishing quite extensively, as have many historians upon whom I relied for oral histories. Fishing and the North Sea still interests me with its twists of gender, sexuality, labour and the more-than-human engagement of extracting the sea (Probyn, 2016; 2014a; 2014b).

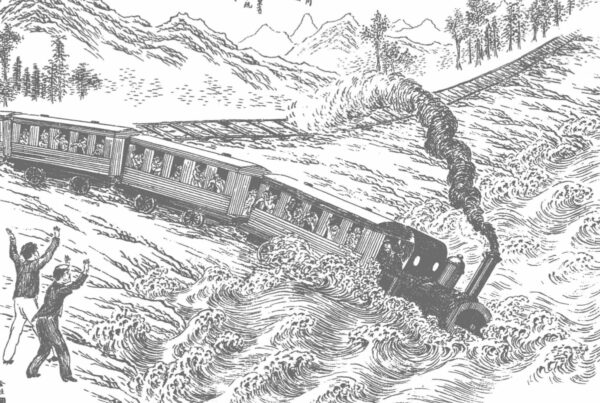

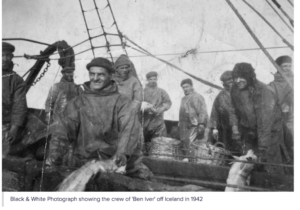

Figure 4: The crew of the Ben Iver

Here I want to focus on that other side of extraction – offshore oil. Sadly, by the 1970s the intense extraction of fish over the centuries, the geo-political battles and quota systems had the industry on its knees. But in October 1970 British Petroleum identified a vast reservoir of crude oil in the Forties field, 110 miles east off the coast of Aberdeen. As The Scotsman put it, “Once home to formidable granite, paper manufacturing and shipbuilding industries and a thriving fishing port, Aberdeen was in the throes of economic decline in the lead up to 1970, but the Forties find would dramatically reverse the city’s bleak fortunes.” (McLean, 2020).

The 1970s were bleak politically and economically in the UK – the time of Thatcher thrashing unions and shutting mines, and the three-day week, thanks to the oil crisis. The rumours of the high life in Aberdeen were rife with tales that sweeping the floor on a rig would earn you hundreds of pounds. The oil rush certainly exacerbated the gulf between rich and poor in the city as it also created new classes. In addition to the wealthy oil (mainly) men who sent their kids to private schools set up for Americans, the offshore workers were extremely well paid, as were the divers who had the most dangerous job in a dangerous business. The bonuses paid when a new exploration was successful were often in the currency of Aberdonian “bling” – highly expensive foreign cars. In the shadows of excess, the multi-generational under and unemployed continued.

As the fishing industry continued to fail, it was easy to guess where the fishers went. As one skipper recounts, “Fraserburgh [up the coast from Aberdeen, had] the highest rate of heroin addiction per head of population anywhere in Britain. These guys who were on the drugs, they were just totally wasted. The good guys that were there [on the boat] got pissed off with all those junkies and they were stolen to the oil industry because the oil was offering good money at the time.” (cited in Djohari and White, 2022).

After the discovery of crude oil in 1970, the rush was on. The following year Shell Expro discovered the giant Brent oilfield in the northern area of the North Sea, east of Shetland. Brent Crude became the benchmark for pricing oil and even though is now fully exploited Brent it is used to set the price of two-thirds of the world’s internationally traded crude oil supplies. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/North_Sea_oil)

The now relatively quiet harbour became a very busy place in the 1970s with rigs, drillers, and divers going out to explore where Aberdeen Maritime Museum sits today. The OSPAR (Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the North-East Atlantic) puts the number of structures in the North Sea at 552, although they are of varying size. But they are all bigger than the tallest skyscrapers. As you can see from the map (Figure 5), the majority of these in the British EEZ in the North Sea are off the coast of Scotland – leading to the fraught political question of “whose” oil it is, which is a central plank to the Scottish Nationalist Party’s campaign for independence, e.g., it’s “Scottish oil.”

Figure 5: North Sea Oil and Gas Fields Base map

To return to the Aberdeen Maritime Museum, dividing the fish and the oil sections and at the centre of the museum, an 8m-tall model of the Murchison oil platform spans three floors. It shows the internal workings of the platform and the complexity of equipment, pipes, separators and pumps.

Figure 6: the Murchison oil platform

Located 240 km northeast of Shetland, the Murchinson was installed in 1979 and began producing oil in 1980, and shut down in 2014. The crude is found in Middle Jurassic (174.1 million to 163.5 million years ago), and Late Jurassic successions (163.5 million to 145 million years ago). This is to say the crude oil that formed up to 174 million years ago was completely exploited in a mere 34 years. As the team have said in other posts, this is a derangement of scales on a massive level. “It will take approximately 25–35 years to dismantle nearly 500 offshore installations and looks set to cost between £45 billion and £77 billion” (Swinback, 2020: 25). To reiterate, it will take about the same time to demolish the rigs as it did to empty the ocean of oil.

European regulations prohibit energy companies from leaving behind any part of a disused platform, and operators must return sites to a clean seabed. So these massive structures are towed away to be decommissioned in various locations, Chittagong in Bangladesh being one of the cheaper options due to the disregard for workers’ safety and low pay.

Some are hopeful that there could be a glimmer of good in this environmental catastrophe. Various types of marine species are found on the underwater jacket of the rigs. Scientists are working on how to turn algae, seaweed, mussels, and anemones into fish feed for Scotland’s numerous salmon farms. (Jordan, 2022). The ethics of feeding marine produce to feed fish is another story for another time.

Image Sources

Figure 1: Aberdeen beach. Val Vannet.

Figure 2: Aberdeen Maritime Museum. Tore Sætre, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Figure 3: Aberdeen Fishing Memorial. Aberdeen City Council

Figure 4: The crew of the Ben Iver. Aberdeen City Council

Figure 5: North Sea Oil and Gas Fields Base map. Maproom

Figure 6: the Murchison oil platform. Love Aberdeenshire

References

Djohari, Natalie, and Carole White. “How the socio-cultural practices of fishing obscure micro-disciplinary, verbal, and psychological abuse of migrant fishers in North East Scotland.” Maritime Studies 21, no. 1 (2022): 19-34.

Jordan, Rain. (2022) “Scientists Aim to Recycle Marine Life Growing on Oil Rigs”. Nature World News. Nov 22. https://www.natureworldnews.com/articles/54262/20221122/scientists-aims-to-recycle-marine-life-growing-on-oil-rigs.htm

McLean, David. “On this day 1970: Huge North Sea oilfield discovery off Scottish coast” The Scotsman. Oct 7. https://www.scotsman.com/heritage-and-retro/heritage/on-this-day-1970-huge-north-sea-oilfield-discovery-off-scottish-coast-2995368

Probyn, Elspeth. (2016) Eating the Ocean. Durham: Duke University Press.

Probyn, Elspeth. (2014a) ‘Women Following Fish in a more-than-human world’, Gender, Culture & Place. 21.5, 589-603.

Probyn, Elspeth. (2014b) ‘The Cultural Politics of Fish: A more-than-human habitus of cultural consumption’, Cultural Politics. 10: 3, 287-299.

Swinbank, Ellie. (2020) “Collecting and displaying the decommissioning of North Sea oil and gas at the National Museums Scotland”. Architectus. 1(6): 25-30.

Wyllie, James, 2018. “Permanent fishing memorial unveiled in Aberdeen”. June 28. https://www.pressandjournal.co.uk/fp/news/aberdeen-aberdeenshire/1508621/permanent-fishing-memorial-unveiled-in-aberdeen/

The crew of the Ben Iver