Extractivism’s latest frontier has reached the remote, deep seabed.

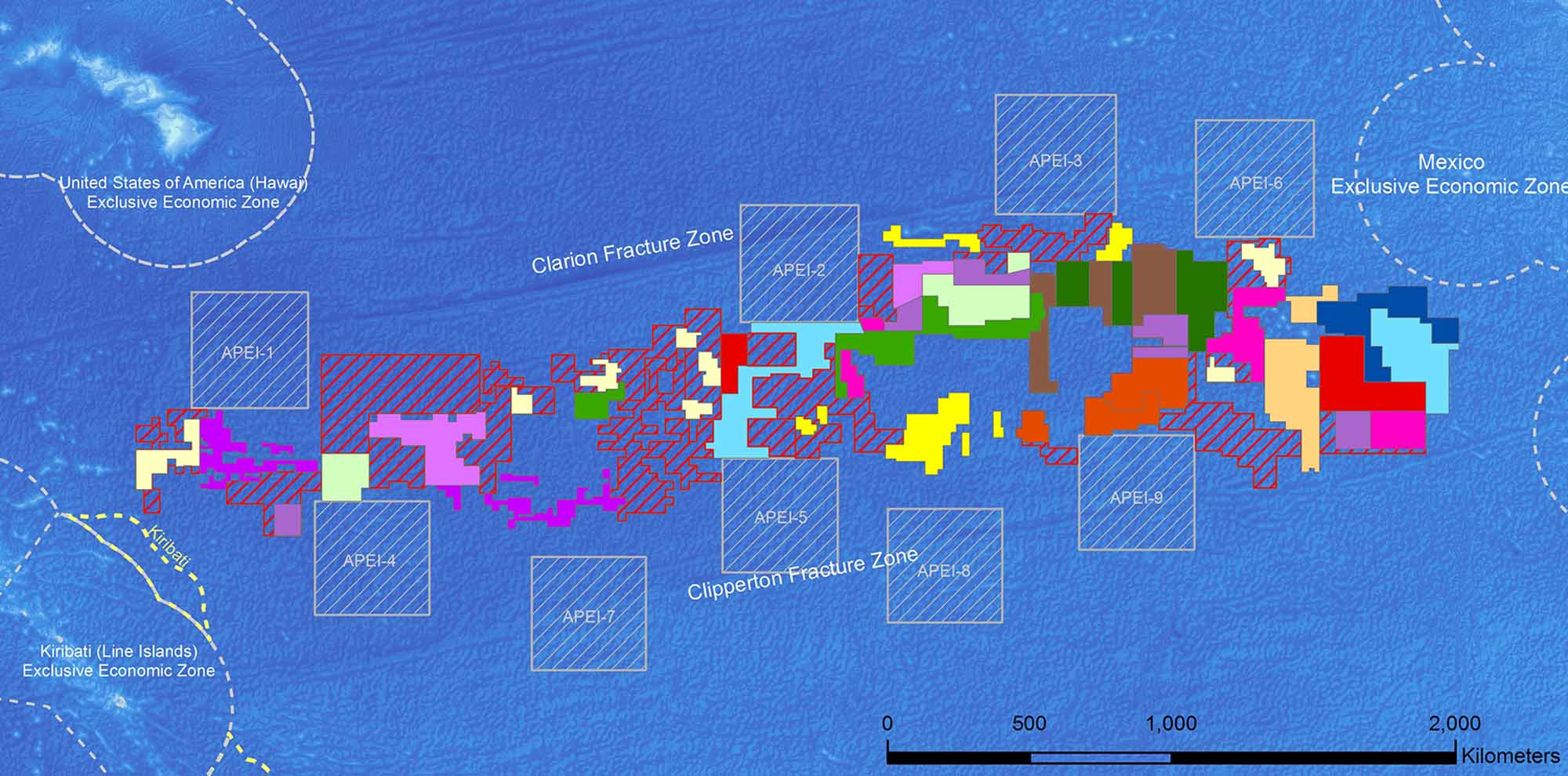

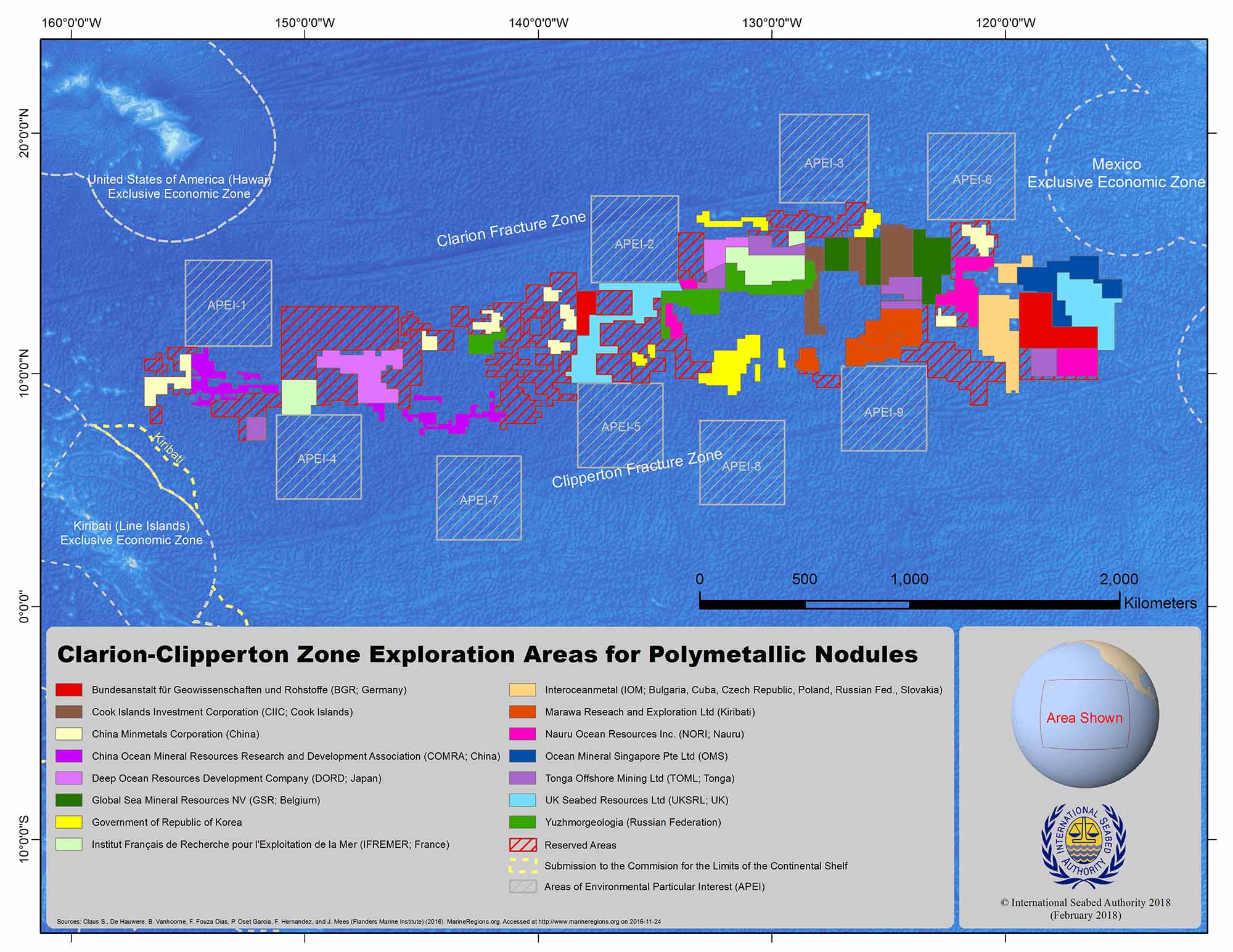

Corporations and their state sponsors are gearing up to mine manganese nodule fields in a nine million km2 region of the Eastern Pacific seafloor, known as the Clarion Clipperton Zone (CCZ). Some of earth’s most diverse ecosystems are associated with nodule fields (Woody 2017), such as those found in the CCZ. Deep-living beings of the CCZ are particularly vulnerable to disturbances due to their slow growth rates, maturation at a relatively old age, long life expectancies, and low or unpredictable recruitment.[1] The effects of 24/7 mining activities in this region would likely be severe and last well beyond human time scales. Civil society groups and conservation organizations are understandably concerned about the potential impacts of mining on these seabed ecologies. Historic and ongoing violences, inflicted by mining corporations on terrestrial environments, indicate that this concern is warranted.[2]

Deep seabed mining would be another assault on the ocean. Though seas are transitional by nature, the scale and cumulative effects of industrialization, such as heat and plastic pollution, manifest oceanic changes of an entirely different order and consequence for planetary habitability. Across the seas and into their depths, for example, anthropogenic climate change already affects circulation, hydrodynamics, temperature levels, and acidity. Humans are also vulnerable to the changes that industrialization forces on the abyssal ocean—what happens in this zone influences whether rains come, plants thrive, temperatures are liveable; or whether the ocean provides sufficient food or enough oxygen for humans and other terrestrial dwellers to breathe. Given human interdependence with the abyssal ocean, our relations with these worlds matter.

Having depleted most of the easy to extract terrestrial supplies of minerals, mining corporations are seeking more profitable sources, and turning their attention to the high grade of minerals at the deep seabed (Spicer 2013). Though the mining industry has its sights on these “blue” riches, its frontier ambitions are meeting with resistance and concern from multiple directions.[3] Proponents claim that seabed mining would benefit countries of the economic south, framing their extractive development ambitions as within terms such as “blue economy” or “blue capital”[4]—as if “blue” makes seabed mining somehow benign.[5] Taking up blue capitalism’s agenda, the International Seabed Authority (ISA), an organization responsible for overseeing seabed development,[6] asserts that seabed mining can expand the resource base for Pacific Island nations and enable growth of their “sustainable Blue Economy.”[7] Responding to the ISA’s assertions, Pacific Island Association of Non-government Organisations, Deputy Executive Director, Emeline Ilolahia argues that, “If mining was the panacea to the economic issues of the Pacific, we’d have solved all our problems long ago. Instead, the environmental and social impacts of mining have made our peoples poorer.”[8]

*This text is adapted from Reid, S. ‘Imagining Justice With the Abyssal Ocean’ (Reid 2022)

[1] United Nations, “The Second World Ocean Assessment: Volume II,” (UN 2021, 279). For more about the risk of species extinction: (Macheriotou et al. 2020, 2666); slow recovery after human-made disturbance: Erik Simon-Lledó (Simon-Lledó et al. 2019, 8040).

[2] For example, the impacts of mining in Bougainville: John C. Cannon, “Decades- Old Mine in Bougainville Exacts Devastating Human Toll: Report,” Mongabay Environmental News, April 17, 2020, https://news.mongabay.com/2020/04/dec- ades-old-mine-in-bougainville-exacts-devastating-human-toll-report/; “One of World’s Worst Mine Disasters Gets Worse – BHP Admits Massive Environmental Damage at Ok Tedi Mine in Papua New Guinea, Says Mine Should Never Have Opened,” Mining Watch Canada, Nov. 8, 1999, https://miningwatch.ca/news/1999/8/11/one-worlds-worst-mine-disasters-gets-worse-bhp-admits-massive-environ- mental-damage-ok.

[3] See Kate Lyons, “Mining’s New Frontier: Pacific Nations Caught in the Rush for Deep-Sea Riches,” Guardian, June 23, 2021, http://www.theguardian.com/ world/2021/jun/23/minings-new-frontier-pacific-nations-caught-in-the-rush

-for-deep-sea-riches; Deep Sea Mining Campaign et al., “Why the Rush? Seabed Mining in the Pacific Ocean,” 2019, http://www.deepseaminingoutofourdepth.org/wp-content/uploads/Why-the-Rush.pdf; Blue Ocean Law and The Pacific Network on Globalisation, “Resource Roulette: How Deep Sea Mining and Inadequate Regulatory Frameworks Imperil the Pacific and Its People,” 2016, http://nabf219anw2q7dgn1rt14bu4.wpengine.netdnacdn.com/files/2016/06/ Resource_Roulette-1.pdf.

[4] See, for example, World Bank and United Nations, “The Potential of the Blue Economy: Increasing Long-Term Benefits of the Sustainable Use of Marine Resources for Small Island Developing States and Coastal Least Developed Countries,” (Washington, D.C.: World Bank and United Nations, 2017); “Achieving Blue Growth Building Vibrant Fisheries and Aquaculture Communities,” Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations, 2018, http://www.fao.org/3/ CA0268EN/ca0268en.pdf.

[5] For related critiques concerning capitalism’s blue turn: John Childs, “Performing ‘Blue Degrowth’: Critiquing Seabed Mining in Papua New Guinea through Creative Practice,” Sustainability Science 15, no. 1 (2020): 117–129; “Surfacing the Agendas of the Blue Economy,” DAWN (blog), March 19, 2019, https://dawnnet.org/2019/03/sur- facing-the-agendas-of-the-blue-economy/; DAWNfeminist, “DAWN/PANG Blue Economy Panel Fiji,” YouTube, March 22, 2019, video, 1:39:59 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6ICLPABe7JE.; Jean-Baptiste Jouffray et al., “The Blue Acceleration: The Trajectory of Human Expansion into the Ocean,” One Earth 2, no. 1 (2020): 43–54; also Elizabeth DeLoughery’s related critique of “blue capital” in this chapter.

[6] The (ISA) is “an autonomous international organization” established under UNCLOS and the 1994 Agreement relating to the Implementation of Part XI of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, December 10, 1982 (July 28, 1994), 1836 UNTS 42 (1994 Implementation Agreement).

[7] ISA Secretary General Michael Lodge speaking at a 2017 workshop jointly hosted by the ISA and the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs in Tonga, https:// www.isa.org.jm/vc/abyssal-initiative-blue-growth. For more on resistance to blue capitalism by Pacific Island nations and communities, see also DAWNfeminist, “DAWN/PANG Blue Economy Panel Fiji.”

[8] “Pacific Island Governments Cautioned About Seabed Mining Impacts,” PIANGO, 2019, http://www.piango.org/our-news-events/latest-news/2019/pacific-island

-governments-cautioned-about-seabed-mining-impacts/. Growing public resist- ance to seabed mining from multiple sectors can be seen, for example, in the cam- paigns of Pacific Blue Line: https://www.pacificblueline.org/.

A map of the Clarion Clipperton Zone in the central Pacific Ocean. Coloured areas are those licensed for mining and shaded squares are areas currently protected from mining. Image adapted from the International Seabed Authority, 2018, sourced from NOAA

Image source URL: https://oceanexplorer.noaa.gov/explorations/18ccz/background/plan/plan.html

References

Macheriotou, Lara, Annelien Rigaux, Sofie Derycke, and Ann Vanreusel. 2020. “Phylogenetic Clustering and Rarity Imply Risk of Local Species Extinction in Prospective Deep-Sea Mining Areas of the Clarion–Clipperton Fracture Zone.” Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 287 (1924): 20192666. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2019.2666.

Reid, Susan. 2022. “Imagining Justice with the Abyssal Ocean.” In Laws of the Sea: Interdisciplinary Currents. London: Routledge.

Simon-Lledó, Erik, Brian J. Bett, Veerle A. I. Huvenne, Kevin Köser, Timm Schoening, Jens Greinert, and Daniel O. B. Jones. 2019. “Biological Effects 26 Years after Simulated Deep-Sea Mining.” Scientific Reports 9 (1): 8040. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-44492-w.

Spicer, Wylie. 2013. “Legalising Seabed Access | Deep Sea Mining: Out Of Our Depth.” October 18, 2013. http://www.deepseaminingoutofourdepth.org/legalising-seabed-access/.

- 2021. “The Second World Ocean Assessment: Volume II.” New York: United Nations. https://www.un.org/regularprocess/sites/www.un.org.regularprocess/files/2011859-e-woa-ii-vol-ii.pdf.

Woody, Todd. 2017. “Seabed Mining: The 30 People Who Could Decide the Fate of the Deep Ocean.” The New Humanitarian, 2017. https://deeply.thenewhumanitarian.org/oceans/articles/2017/09/06/seabed-mining-the-24-people-who-could-decide-the-fate-of-the-deep-ocean.